Obituary: Robert Ford

His Holiness the Dalai Lama presenting Robert Ford with ICT’s Light of Truth Award in April 2013.

Robert Ford, who was serving the Tibetan Government when Communist Chinese forces began their invasion, has died in London on September 20, 2013 at the age of 90.

Robert Ford was working as a radio officer in Kham for the government of Tibet in the 1940s, in charge of setting up Tibet’s first broadcasting station and training Tibetan radio operators. He was captured by advancing PLA troops in 1950 after an earthquake cut off a planned escape route. During nearly five years of imprisonment, Ford was subjected to interrogation and ‘thought reform’ and was in constant fear of execution. He spent four years in jail before the Chinese allowed him to write a letter home to his mother telling her he was alive. After being sentenced in 1954 to a 10-year term for “espionage,” he was released in 1955 and expelled.

Robert Ford received ICT’s Light of Truth award from the Dalai Lama in April 2013 in acknowledgment of his tireless advocacy on behalf of Tibet for more than half a century. Mr. Ford said: “I am a member of a rather exclusive club of Westerners who have the privilege and good fortune to see, know and witness a free Tibet before 1950. I spent some of the happiest days of my life in Tibet. The Tibet that I found when I first went there in 1945 was vastly different to the Tibet of today. It was an independent country with its own government, its own language, culture, customs and way of life. … To me as an outsider, the most remarkable feature of Tibetans was their devotion to their religion and their unswerving support for His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Another striking feature was their remarkable self-reliance both in the material and the spiritual sense. Tibet valued its self-imposed isolation and independence. Its simple wish was to be left alone to run its own affairs in the way that it thought best.” (View footage of the full speech »)

Robert Ford leaving Gangtok, Sikkim, bound for Tibet.

In late 1945, Mr. Ford transferred to the Political Office in Gangtok, Sikkim and remained there until 1947, when India became independent. It was then that he was able to fulfill an ambition to return to Tibet. He was asked by the Government of Tibet to join its service, to start Tibet’s first broadcasting station, train Tibetan radio operators and set up a radio communications network throughout Tibet. He was the first Westerner to be employed by the Government of Tibet and given an official rank. In Britain, newspapers at the time dubbed Ford “the loneliest Briton in the world” because of his remote posting.

In Lhasa, Ford, known affectionately to Tibetans as ‘Phodo Kusho’ (Ford Esquire or Ford Sir), built and opened Radio Lhasa, and for the first time, Lhasa was able to broadcast to the outside world. After a year in Tibet’s capital, Ford was asked to go to Chamdo[2] in Kham, eastern Tibet, to expand the Tibetan radio communications network. As well as creating a radio link between Lhasa and Chamdo, he and his trainees helped the then Governor General of Kham, Lhalu Tsewang Dorje, improve defence in Chamdo and the surrounding area.

Ford was also called upon on occasion to administer urgent medical assistance, sometimes treating Tibetans involved in the resistance against the Chinese. He wrote: “I had no surgical instruments or experience, but I was the best doctor in Chamdo because I was not a Tibetan Buddhist and had learnt first aid in the Boy Scouts.” He established a radio link with a tailor named Jefferies in Burton, Staffordshire, which enabled his parents to speak to him every Wednesday.

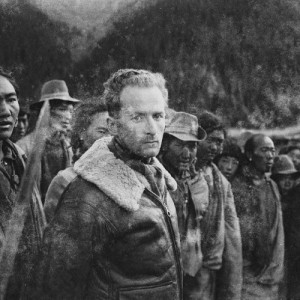

Robert Ford upon capture by Chinese troops in 1950.

In a microblog posted on September 23, Tibetan writer and blogger Tsering Woeser wrote: “Mao had long ago announced to the world that imperialist forces had invaded Tibet, and therefore the People’s Liberation Army must march on Lhasa to bring the people of Tibet back to the big family of the People’s Republic of China. But while the PLA advanced forces prepared to make war on Chamdo, the only ‘imperialist’ force entrenched there was a single Englishman named Ford. Even across the entirety of Tibet at the time there were very few Westerners!”

Ford could have left Tibet safely, but did not want to abandon the Tibetan people. His radio link was the only possible way [Tibetans] could get to know progress of the invasion. (The only alternative would have been by mounted courier who, riding continuously day and night, stopping only to change horses, could have done it in 15 days.) He developed a plan for an emergency escape route to the south across the pass into India if they were cut off by Chinese troops. But a devastating earthquake rocked the entire border area and the route became impassable.

Ford wrote: “I doubt whether there were more than 3,000 Tibetan troops on the frontier area at the time and, judging by news that came our way, they were being confronted by a force which probably outnumbered them 100 to one. News of small-scale clashes came from the Yangtse River area which was five days’ march away. Although heavily outnumbered, the Tibetans fought courageously – fighting for the Dalai Lama. On several occasions we heard that Chinese troops had leapt into the icy river waters to escape the Tibetan soldiers.” (The Daily Mail, 2 July 1955).[4]

As troops closed in, Ford and fellow Tibetan officials left Chamdo early in the morning and stopped to rest and water their horses at a monastery where Tibetan officials had sought refuge. He observed in his book that: “The Tibetan Army was not designed for retreat. When troops went to the front line they took their families with them [with] household goods and personal belongings piled up on yaks and mules. There were tents, pots and pans, carpets, butter-churns, bundles of clothes, and babies in bundles on their mothers’ backs. […] What made it more remarkable was the absence of panic or even anxiety.”

Just prior to his capture, Ford thought about whether he could still escape southwards through Lhasa, but the ponies were exhausted, and the route was treacherous.

He wrote: “I resigned myself to capture with the others – all of them Tibetan officials from Chamdo and their servants. Even the monks by then were becoming agitated, running round and round in near-panic, hardly able to compose themselves to prayer. The following afternoon one young monk came running in from the valley and propelled me towards a window. My heart missed a couple of beats as I saw a column of perhaps 200 Chinese troops riding steadily up the valley, led by Khamba guides. They carried rifles, the familiar Russian-type tommy-gun, and a type of Bren-gun. They halted a few hundred yards from the monastery, deployed, and threw a cordon round the buildings. We were surrounded.” (‘Captured in Tibet’).

Chamdo was of strategic importance to Beijing; the Communist authorities gained control of central Tibet when Chamdo, eastern Tibet’s provincial capital, fell to the People’s Liberation Army on October 7, 1950.[5]

Upon arrest, Ford was accused of espionage, spreading anti-communist propaganda and causing the death of a Tibetan called Geda Lama.[6] His book gives a vivid and detailed description of the methods of psychological intimidation and ‘thought reform’ used by the Chinese authorities to gain confessions, break prisoners, and even make individuals believe they were guilty of what they were accused of. Writing about one particular interrogator, Kao, Ford said: “Sometimes he interrogated me in a different room. It sounds a little thing, but even the slightest change in prison routine aroused alarm. The guard led me along the corridor – and then turned right instead of left. Or he took me across a courtyard towards the sort of wall a firing squad might use. Once I was taken outside the prison and made to walk towards a wood. I cannot describe the fear I felt. […] Every morning when I woke I wondered if this was the day I would be shot.”

Ford was released in 1955, given six Hong Kong dollars, and sent across a rickety wooden railway bridge into Hong Kong, where he was met by a British policeman, whose first words seemed to Ford: “irreverently casual. ‘Everest has been climbed,’ he said, when I asked him what was happening in the world. ‘We’ve won back the Ashes.’ The startling thing was not merely that non-political events could be considered as news but that he did not invest them with any political significance. Everest had been climbed by a handful of brave individuals, not because a Party was glorious or a Chairman great. England’s victory over Australia at cricket was not due to the correct application of Marxist-Leninist principles.” Ford was taken by sea to Singapore and from there flew back to England.[7]

Following his release, in 1957 Ford joined the British Diplomatic Service. During his career he served in the Foreign Office in London and at various posts around the world; in Vietnam, Indonesia, the USA, Morocco, Angola, France, Sweden, and finally as UK Consul-General in Geneva, Switzerland, from where he retired in 1983. In 1982 Mr Ford was awarded a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire).

Ford married Monica Tebbett, a childhood friend from a nearby village in Staffordshire who was at the time working for the United Nations in New York, in 1956. “We met again and fell in love,” said Ford, according to a local village website. They were married for 55 years.

Ford remained active in retirement, enjoying hiking and travel, and only stopped skiing at the age of 86. His retirement also allowed him more time for active support to the Tibetan cause. He was a founder member of the Tibet Society in 1959 and remained a Vice President for the rest of his life. He wrote extensively and lectured on all aspects of Tibetan and Chinese affairs in the UK, the rest of Europe, Australia, and the United States.

In 1992, he undertook a lecture tour in India, at the request of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, speaking at military and civilian institutions as well as in the Indian Parliament. Ironically, he and his wife had to cut short their tour after they were detained in Dharamsala by the Indian authorities as their visit had coincided with Chinese Premier Li Peng’s official visit to India.

In 1996, Ford organised the first meeting between the Dalai Lama and a member of the British Royal family. His Holiness met the late Queen Mother together with Ford at Clarence House.

Ford is survived by his two sons, Martin and Giles, and three grandchildren, Emma, Candice and Nicholas, who joined him in a private and moving ceremony to receive ICT’s Light of Truth award in Fribourg, Switzerland, on April 13 (ICT report, ICT Light of Truth Award ceremony brings together eminent individuals with historic connection to Tibet). The occasion became Ford’s last meeting with the Dalai Lama, who regarded him as a close friend.

Following the ceremony, Mr. Ford said: “I had the great privilege of having my first audience with His Holiness in Lhasa in the early 1940s. He was only 11 years old; I feel so honored to receive the Light of Truth award from His Holiness almost 70 years later. One of the advantages of living a long life like me is that you witness some extraordinary changes, some of which earlier in your life you would never imagine could have happened. This gives me great hope and I wish with all my heart that we will once again see a return to a free Tibet.”

In March 2013, Thubten Samdup, the Dalai Lama’s Representative in London, organised a reception for Ford’s 90th birthday during which he was presented with the last of his salary, a 100 Srang note of Tibetan currency. Ford was imprisoned by the Chinese authorities before his salary was due. Representative Samdup said: “We heard Robert was about to turn 90, so we thought it best we pay him what we owe. We’re sorry it has taken so long to give him his final wage, but there has been extenuating circumstances.” Ford was quoted as saying, “I had jokingly reminded the Tibetans recently that I had not been paid and they’d better hurry up. It’s an honour to receive this from the Tibetans. It was a very special, sometimes difficult, time in my life.”

Mr Ford was visibly moved as Tibetans gathered to wish him a happy birthday and pay their respects to him.

Bhuchung Tsering, Interim President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: “We offer our deepest condolences to Robert Ford’s family. Tibetans everywhere will remember Robert Ford for his service to Tibet, and even having to suffer incarceration because of it, at a turning point in Tibetan history. ICT is honored to have been able to bestow our the Light of Truth award to him.”

Tsering Woeser on the passing of Robert Ford

Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser posted a series of microblogs on her Twitter site, @degewa, on September 23, about the passing of Robert Ford, giving new perspectives from senior Tibetans in China. Woeser is a prolific blogger, poet and author who documents contemporary Tibetan experience in a broader context of the Chinese presence in Tibet. Woeser also posted some photographs of Ford’s capture.

Woeser’s microblogs about Robert Ford follow below, translated into English by ICT:

Robert Ford, arrested.  Ngabo Ngawang Jigme and Wang Qimei.  Robert Ford, captive. |

Robert Ford – This Englishman appeared in Lhasa and Chamdo sixty years ago, and he most likely had the strangest experience of any of the Westerners who have ever visited Tibet. Because there was never another Westerner like him, for these 60 years he has continuously been called a representative of imperialism in Tibet and has been framed as a toxic influence that turned eminent monks into foreign spies. He was even the so-called reason for the ‘Liberation of Chamdo.’

Three years ago the redneck9 Communists celebrated the ‘60th Anniversary of the Liberation of Chamdo,’ and Tibet Television Studio interviewed Yin Fatang, the former Party Secretary of Tibet who has spent his life concocting endless “class enemies.” He brought up the old claim that the great ‘patriot’ Geda Rinpoche was killed by Robert Ford, a British spy. But I heard an old 18th Army soldier embarrassedly admit that Ford was a scapegoat, and that at the time he had been ordered to claim that Ford was such a character.

I also asked Mr. Phuntsok Wangyal. As the first Tibetan Communist, and having accompanied the Chinese Communist army into Tibet, he was at the time a member of the Tibet Work Committee, Chamdo area deputy secretary, a position higher than Yin Fatang. Mr. Phuntsok Wangyal said that he had seen both Geda Rinpoche and Ford. The young Englishman was employed by the Tibetan government and spent two years in Chamdo as a telegraph operator. At that time the Tibetan government representative stationed in Chamdo was Lhalu Tsewang Dorje.

Mr. Phuntsok Wangyal recalled that in the early years the retreating Communist army came into contact with Geda Rinpoche as they moved through Kham during the Long March because he was recognized as the Vice Chairman of the “Tibetan Autonomous Government.” It’s as if he were appointed Vice Chairman of Xikang province today. He had a good impression of the Chinese Communist Party and went to Chamdo to advise them, but on the way he had diarrhea and took an overdose of Tibetan medicine, and the excessive minerals in the Tibetan medicine caused stomach bleeding, resulting in his death within two weeks of arriving in Chamdo. But at first there were no claims that Ford was involved in the death of Geda Rinpoche.

Two months later the ‘Chamdo campaign’ to defeat the Tibetan army ended quickly, and as the People’s Liberation Army held a victory rally Mr. Phuntsok Wangyal heard them shouting slogans like “Down with the British spy Ford!” and “Down with the imperialists!” He soon learned that Ford had been identified as the perpetrator of the Geda Rinpoche poisoning, which surprised him greatly.

At the time a captive Chamdo official told Mr. Phuntsok Wangyal that Ford was framed, that there was no basis for this and that Ford never came close to Geda Rinpoche on his own. Because of this Mr. Phuntsok Wangyal went to the deputy political commissar of the 18th Army and Chamdo area committee secretary Wang Qimei for clarification, but Wang Qimei just sighed twice.

In 1954 Kalon Liushar Thubten Tharpa of the Tibetan government accompanied the Dalai Lama to Beijing, and sent a letter to the State Ethnic Affairs Commission seeking to redress Ford’s grievances. Ford had spent more than three years locked up in prison in Chongqing on a ten-year sentence, before his early release in May 1955.

Many years later, Tibet’s most famous Communist Party collaborator Ngapo Ngawang Jigme [the governor of Chamdo at the time of its fall to the PLA] told Mr. Phuntsok Wangyal that “these claims were completely groundless.” Today, more than sixty years later, elderly historian Mr. Phuntsok Wangyal said in a firm tone, “that Ford case was completely fabricated.”

It’s like this: Mao had long ago announced to the world that imperialist forces had invaded Tibet, and therefore the People’s Liberation Army must march on Lhasa to bring the people of Tibet back to the big family of the People’s Republic of China. But while the PLA advanced forces prepared to make war on Chamdo, the only ‘imperialist’ force entrenched there was a single Englishman named Ford. Even across the entirety of Tibet at the time there were very few Westerners!

Nevertheless, historical opportunities always arise, and since Geda Rinpoche was a ‘patriot,’ his timely death should therefore somehow be related to imperialist oppression. Ever since, whenever historical grievances are needed to counter ‘Free Tibet’ [representations], Chinese websites always bear the words: “The intelligence agencies of the US, UK, and other countries were involved in the insurgency. Ford, who personally killed patriotic Tibetan leader Geda Rinpoche was captured.”

Heinrich Harrer, an Austrian who lived in Tibet for seven years, recalled Robert Ford as a telegraph operator who was employed by the Tibetan government who lived in Lhasa for a year or two before going to Chamdo. He loved dancing, and introduced samba dancing to Lhasa. In Ford’s own recollection, after he went to Chamdo he received letters and gifts from many curious people around the world, and of course he replied to them, and after he was captured these became evidence that he was engaged in espionage.

罗伯特•福特(Robert Ford)这个在六十多年前出现在拉萨与昌都的英国人,恐怕是所有到过藏地的西方人中最具离奇色彩的。因为没有第二个西方人像他这样,在这六十年多里从未间断地被说成是帝国主义在西藏的代表,且被构陷为毒害西藏高僧的外国特务,甚至成了“解放昌都”的所谓缘由。

三年前土共庆祝“昌都解放六十周年大庆”,西藏电视台采访那个毕生炮制了无数个“阶级敌人”的前西藏自治区党委书记阴法唐,又提起了伟大的“爱国人士”格达活佛被英国特务福特害死的旧话。但我曾听一位老十八军军人不好意思地承认:福特是个替死鬼,当时我们需要把他说成是这么一个角色。

我又问过平措汪杰先生。作为西藏最早的共产党人,以及与中共军队一起进入西藏的藏人,当年他是西藏工委委员、昌都分工委副书记,职务高于阴法唐。平汪先生说他见过格达活佛,也见过福特,是个年轻的英国人,受雇于西藏政府,在昌都做了两年的电报员,当时西藏政府派驻昌都的总管是拉鲁•次旺多吉。

平汪先生回忆说,早年与逃经康区的中共红军接触过的格达活佛,因曾被认可是“博巴自治政府”的副主席,如今又被委任为西康省副主席,对中共抱有好感而赴昌都劝和,但因腹泻服下过量藏药,而含有矿物质的过量藏药让他胃出血,结果到昌都才两周就不治而死,不过起先并未宣称格达活佛的死与福特有关。

两个多月后,“昌都战役”以藏军溃败而很快结束,当平汪先生听到解放军在庆功集会上呼喊“打倒英国特务福特”、“打倒帝国主义分子”的口号,才知道福特已被确定为毒死格达活佛的凶手,这让他很是惊讶。

当时,一位被俘的昌都官员对平汪先生说这是诬陷,因为没有任何根据,而且福特根本没有单独接近过格达活佛。为此平汪先生向十八军副政委、昌都分工委书记王其梅澄清过,但王其梅只是“哦哦”了两声。

1954年,西藏政府噶伦柳夏•土登塔巴随达赖喇嘛到北京,专门致信国家民委,为福特申冤。而福特已被关在位于重庆的监狱三年多,本被判刑十年,1955年5月提前获释归国。

多年后,西藏上层中与中共合作最为著名的人士阿沛•阿旺晋美对平汪先生说:“这完全没有根据”。六十多年后的今天,历史老人平措汪杰先生用确凿无疑的语气说:“福特这个案子完全是一手制造的”。

是的,毛主席早就向全世界宣布了,帝国主义势力侵入了西藏地区,为了让西藏人民回到中华人民共和国大家庭,解放军必须进军拉萨。而解放军的先遣部队已经做好了在昌都打仗的准备,可是盘踞在那里的帝国主义势力,只有一个叫福特的英国人,即便是在全藏地,当时也没几个西方人啊。

然而历史机遇总归是会降临的,格达活佛既然是“爱国人士”,那么他恰逢其时的病故就应该与帝国主义分子的迫害有关。于是乎,一桩历史冤案便应“解放西藏”的需要产生了,至今中国的网站上还赫然写着:“美、英等国的情报机构参与了叛乱。亲手杀害爱国藏民首领格达活佛的英国人福特被抓获。”。

在拉萨住过七年的奥地利人哈勒曾回忆,受雇于西藏政府任电报员的英国人罗伯特·福特,在拉萨住过一两年再去了昌都,嗜好跳舞,森巴舞就是他引进到拉萨的。福特自己回忆,他到昌都以后,收到世界上很多好奇之人的信件和礼物,他当然要回复,结果他被俘后,这些竟然全都成了他搞间谍活动的证据。

Footnotes

[1] The UK was until 2008 the only UN member to stop short of recognizing China’s sovereignty, and to use the formula ‘suzerainty’ instead. This description of Tibet’s status in the era before the modern nation-state was close to the findings of most historians. With a statement by former Foreign Secretary (under the previous Labour government) David Miliband on October 29 2008, Britain renounced this position as an “anachronism” and a “colonial legacy”, in apparent deference to long-standing concern by the Chinese government. The Chinese government welcomed the change in language (http://www.china.org.cn/international/news/2008-11/02/content_16700275.htm).

[2] Chamdo (Chinese: Qamdo) is now incorporated in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

[3] The book was re-published in 1990 with a preface by His Holiness the Dalai Lama and an epilogue by the author entitled ‘The Occupation’.

[4] Full article can be read at: http://www.rolleston.org.uk/memory/rwford.htm

[5] Chamdo is still important to the Chinese authorities, who regard it as “a strategic bridge between the Tibet Autonomous Region and the neighboring provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan and Qinghai.” (Tibet Daily, April 17).

[6] The case against him was completely fabricated. See translation of Tsering Woeser’s observations following this report. In a microblog published on September 23 (2013), Tibetan writer Woeser (@degewa) wrote: “In Ford’s own recollection, after he went to Chamdo he received letters and gifts from many curious people around the world, and of course he replied to them, and after he was captured these became evidence that he was engaged in espionage.”

[7] An account of his reunion with his parents is given on the Rolleston-on-Dove village website: http://www.rolleston.org.uk/memory/rwford.htm

[8] Woeser’s father was a People’s Liberation Army photographer and, based on hundreds of his photographs taken in Tibet during the Cultural Revolution, Woeser has conducted in-depth interviews and written articles about Tibet’s contemporary history. In 2006, the Taiwanese publisher “Locus” published Woeser’s two books ‘Forbidden Memory’ and ‘Tibet Remembered’. ‘Forbidden Memory’ is a commentary on the photos that her father took during the Cultural Revolution as well as her research. ‘Tibet Remembered’ is an oral history of people affected by the Cultural Revolution in Tibet. The two books have been referred to as “the so far most complete and comprehensive photographic record of Tibet during the Cultural Revolution”. See: http://highpeakspureearth.com/2013/the-tibetan-version-of-forbidden-memory-tibet-during-the-cultural-revolution-is-now-available-for-download-free-of-charge-by-woeser/

[9] The Chinese term tugong, literally meaning ‘red neck’, is a derogatory term for the Communist Party

[10] Geda Lama was known as a ‘patriot’ from the Chinese Communist perspective, but not by Tibetans Ford worked with