- A system of intense security and forced assimilation that Chinese Communist Party official Chen Quanguo first developed in Tibet is now being used in Xinjiang, where Chen and his forces have locked up at least 1 million ethnic Uyghurs and Kazakhs in prison camps because of their ethnicity, culture and religion.

- Chen’s system combines hyper-securitization and militarization with efforts to accelerate the political and cultural transformation of local people. Its stated aim is “breaking lineage, breaking roots, breaking connections, and breaking origins” of Tibetans and Uyghurs.

- A feedback loop has developed in which surveillance introduced in Tibet is then imposed in Xinjiang, and new intrusive measures that debut in Xinjiang are then applied in Tibet. For example, following the installation of QR codes on the homes of the Uyghur Muslim community in order to get instant access to the personal details of people living there, the same devices that officials can scan with their smartphones have now been installed on homes in rural areas of Kardze (Ganzi) in Tibet.

- While the well-documented internment of Uyghurs in large-scale camps over the past year has not been replicated in Tibet, prison facilities in the Tibet Autonomous Region have been expanded and modernized, and the risk of imprisonment is higher, with even moderate expressions of Tibetan cultural and religious identity now considered criminal offenses.

- There is more widespread use of torture directed at a broader spread of society involving comparable methods to penalize Tibetans and Uyghurs, such as the use of the spiked clubs known as ‘wolf’s teeth’ and the ‘tiger chair,’ which has been described by former Tibetan prisoners as one of the worst forms of torture.

- A “grid management” program that Chen implemented in Tibet first focused on profiling and targeting individuals regarded as potential problems for the Chinese government. That program has now been expanded in scope and potentially targets all Tibetans and all Uyghurs—entire ethnic populations—with the help of new technology that uses facial recognition to distinguish “ethnic minorities” from Han Chinese.

- Surveillance technologies that have sparked outrage internationally because of their use in Xinjiang were trialed in Tibet. Hikvision, which provides equipment for the massive prison camps in Xinjiang and is now banned by the US and Australian governments, has offices in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa and provided surveillance for the Qinghai-Tibet railway.

- An initiative led by Chen to promote intermarriage between ethnic Chinese and Tibetans, which failed to make a deep impact on Tibetan society, has been developed further in Xinjiang as part of a “pairing up” scheme for Chinese officials and cadres with Uyghurs.

- New and closer collaboration between Xinjiang military and security officials in the border areas of Tibet reflects narratives propagated by the Chinese government—bearing little or no relation to reality—that the two major “ethnic minority” regions of China present a “grave and present danger” to China’s overall security.

Chen Quanguo presenting security forces with khatags (blessing scarves) in Tibet, prior to his transfer as Xinjiang Party chief. (Photo: Tibet Daily)

Executive Summary

Reports on the current situation in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR)[1] describe a climate of expansive surveillance and control, the mass detention of at least 1 million Uyghurs and Kazakhs in re-education camps and an effective information vacuum.[2] In August 2018, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed grave concern over “[n]umerous reports of detention of large numbers of ethnic Uighurs and other Muslim minorities held incommunicado and often for long periods, without being charged or tried, under the pretext of countering terrorism and religious extremism.”[3] The international community has been justifiably concerned about Uyghurs and Kazakhs who have been severely targeted because of their ethnic identity, culture and religious practice. In November 2018, 15 western ambassadors in Beijing undertook the unprecedented move of writing to Chen Quanguo, the Party Secretary in Xinjiang, to request a meeting to discuss the current situation there.[4] As Chen is the party secretary leading policy design and implementation in Xinjiang, the 15 western ambassadors have good reason to seek him out.

While the latter appears to be a promising development, it is questionable how forthcoming Chen would be at such a meeting. To best understand what is unfolding in the XUAR and the motivation driving Chen and the Chinese Communist Party’s policies, observers should look to Tibet, where Chen previously served as the party secretary for the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) from August 2011 to August 2016. Chen’s policy goals and projects in Tibet offer insights into the roots of what is being called the ‘Xinjiang model’ of repression, in particular the emphasis on cultural assimilation and the construction of an extensive architecture of surveillance and control. The scholars Adrian Zenz and James Leibold even point out that Chen Quanguo rolled out Tibet’s securitization strategy in Xinjiang within one year of his tenure, accomplishing what took him five years in the TAR.[5]

Tibet and Xinjiang share many similarities. Both are expansive regions with a harsh terrain inhabited by predominantly non-Han ethnic populations with distinct cultural and religious practices. As border regions, their stability and security are of interest to the Chinese leadership. Potential threats to social cohesion and stability, such as a separate identity, can be treated as national security threats that require extra-ordinary— sometimes military— responses.

First in Tibet, and later in Xinjiang, Chen and the Chinese state adopted a new guiding principle for managing its restive border populations. The principle assumes all Tibetans and Uyghurs— because of their distinct and separate sense of ethnic identity and culture— pose an existential threat to social stability and national security. In essence, Chen securitized Tibetan and Uyghur ethnicity. Securitization describes the act of framing an issue (Tibetan and Uyghur ethnicity) as an existential threat, requiring extraordinary countermeasures.[6] By securitizing Tibetan and Uyghur ethnicity, Chen sought to legitimize the use of rule-breaking behavior, such as actions to prevent ethnic threats from materializing. The underlying assumption of ethnic guilt is a marked shift from earlier policies which sought to endear local populations with economic inducements and only target active dissidents or individuals with suspicious histories, such as known travel to India. Guided by this assumption of guilt and a desire to take proactive action to secure control of Tibet (and later Xinjiang), Chen pursued a two-pronged approach to manage the threat, launching a campaign to reduce ethnic difference by accelerating assimilation and building a dense security architecture to reinforce this process.

This image from a video that emerged from Tibet shows Tibetan nuns, apparently evicted from Larung Gar, being ‘re-educated.’ They are wearing military fatigues and singing a Party song, ‘Chinese and Tibetans, children of one mother’.

Accelerate assimilation by ‘breaking ethnic lineages and cultural roots’[7]

In the context of China, assimilation describes the process of non-Han populations adapting to the cultural milieu of the majority Han society. This often entails reducing unique ethnic and cultural differences, such as the use of a distinct language, religious practices, social norms and work cultures. In Tibet, the policy of accelerated assimilation is evidenced in campaigns that have sought to ‘break ethnic lineages and cultural roots,’ for example, through:

- Blocking external media sources, distributing government propaganda and increasing government presence in community and public spaces

- Re-education programs (including compelling monks to lead the programs)

- Intermarriage initiatives

Reinforce assimilation by building a security architecture that enables sophisticated surveillance, control and coercion

During his tenure as the party secretary of the TAR, Chen established a security architecture that consisted of:

- Police stations/check points located 300-500 meters apart in urban areas

- An integrated neighborhood grid surveillance system collating human intelligence, real-time face-recognition surveillance footage and big data analytics

- Use of torture and collective punishment for coercion

In addition to their common experience under the rule of Chen, Xinjiang and Tibet also have a special feedback relationship where a perceived policy success in one region is transplanted to the other and vice versa.

This report breaks down Chen’s policy approach and model in Tibet. It begins with an introduction to Chen and a timeline of his tenure in Tibet and Xinjiang. This is followed by an analysis of the underlying principle guiding Chen’s policy approach to managing Tibet and Xinjiang and provides detailed examples of his two-pronged policy of accelerated integration and mass surveillance and control.

Chen Quanguo

Chen Quanguo, the Chinese leader most associated with developing the ruthless machinery of compliance in both Tibet and Xinjiang, originates from Henan Province.

Chen was appointed as party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region in August 2011 under Hu Jintao, who preceded Xi Jinping as China’s party secretary and President. He shares a similar political trajectory to Hu, who also proved himself to the party by presiding over a crackdown in Tibet—in Hu’s case, the imposition of martial law in March 1989 after a series of Tibetan protests. In August 2016, due to his perceived successes in the TAR, Chen was announced as the party secretary of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.[8]

Compared to other prominent Chinese leaders, available biographical information on Chen is limited. Despite this, he has developed a reputation within Chinese media for his hardline approach to managing Tibet and Xinjiang, with many attributing to him the “Chen Quanguo effect.”

Timeline of Chen’s tenure and key political events in Tibet

- May 2011: Appointed party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region

- August 2011: Rolled out his first security innovation, the “convenience” police stations, which are part of a “grid-style social management” system

- October 2011: The TAR advertised 2,500 police positions, with 458 of them designated for Lhasa’s new police stations

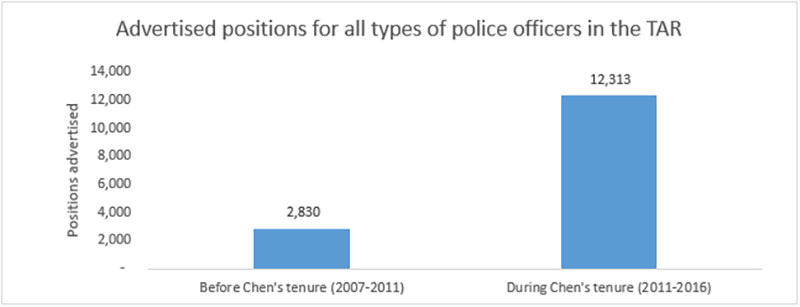

- Between the autumn of 2011 and 2016: The TAR advertised 12,313 policing-related positions—more than four times as many positions as the preceding five years

- Between 2011 and 2015: More than 7,000 party cadres described as “outstanding” and members from the TAR were sent to 1,787 Tibetan Buddhist monasteries to expand party work, and more than 20,000 party members and cadres were sent to Tibetan villages and townships

- August 2016: Transferred to Xinjiang

A new approach: assuming guilt and securitizing an ethnic population

After the March 2008 protests that erupted in Lhasa and the rise of self-immolations from 2009, policymakers and state officials sought to rethink the governance of Tibet. Policy debates around the issue underlined the urgent need to control the ethnic tensions in Tibet and also Xinjiang. For example, Hu Lianhe[9] warned of the threat of ethnic division in undermining Chinese sovereignty and called for greater assimilation. Ma Rong, an academic and influential policy commentator advocated for ethnic difference to be de-emphasized and Tibetans to be treated according to their socioeconomic status.[10]

Within this policy climate, combined with the spread of self-immolations across the Tibetan plateau, Chen adopted a hard-line approach to Tibetan governance. He pursued a strategy that assumed all Tibetans, because of their distinct ethnic identity and culture, posed a threat to national security. In adopting this assumption, Chen securitized the Tibetan ethnicity, treating an entire ethnic group as a threat to the state. The assumption of guilt is significant, as it is a marked shift from earlier policy positions that only targeted active dissidents. To manage the population-wide threat, he adopted a two-pronged approach: 1) accelerate assimilation and 2) build a security architecture to reinforce assimilation.

Accelerating assimilation: “break ethnic lineages and cultural roots” to create compliant citizens and Party subjects

Chen’s policies sought to secure Tibet by reducing ethnic and cultural difference. He focused on accelerating cultural assimilation and deployed a campaign to “break ethnic lineages and cultural roots” to create compliant citizens and party subjects. A work team member who was in Tibet at the time of Chen’s tenure told the International Campaign for Tibet that the Chinese authorities had realized that without controlling Tibetans’ thinking and what he characterized as the “consciousness sphere,” the mission of achieving “long-term political stability” in Tibet would be impossible.[11]

With this goal in mind, Chen’s campaign sought to monopolize information and create a “correct” way of living. Chen introduced policies to control the flow of information, increase party presence in public and private spaces and encourage Chinese nationalism through re-education camps. For example, early in his tenure Chen introduced measures to constrain the flow of information. He stifled Tibetan news sources and replaced them with Communist Party outlets. One official media report stated that since 2011, more than 600 million yuan (US$86 million) had been allocated in order to saturate Tibetan monasteries with party newspapers, radio and television broadcasts.[12] Chen aimed to ensure “no voices and images of enemy forces and Dalai clique can be heard or seen.”[13] As commentators such as Tsering Woeser, a prominent Tibetan writer, have noted, the Chinese government is seeking to replace loyalty to the Dalai Lama in Tibetan hearts and minds with allegiance to the Chinese Communist Party-state and, in doing so, “obliterate memory”[14] and undermine Tibetan nationality at its roots.

A recent visitor to eastern Tibet noted that even in Eastern Tibet, the Tibetan population were mostly unaware of the scale of mass internment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, saying: “There is no way they can know—information flow is entirely blocked, and they have no access to news about anywhere else. Tibetans are completely locked in and isolated.” Equally, information coming out of Tibet was and continues to be limited, as sharing images or details of protests and incidents from inside Tibet is criminalized and can also incriminate family and friends. For example, Yonten Gyatso was arbitrarily arrested in October 2011 and detained without sentence for eight months. He was later sentenced in June 2012 to seven years in jail for “sharing pictures of nun Tenzin Wangmo and information related to her self-immolation protest with [an] outsider.”[15] In March 2012, ahead of an annual parliamentary session and anniversary of the failed Tibetan uprising in March 1959, Chen urged authorities to tighten surveillance of the internet and mobile communications, cautioning “Mobile phones, internet and other measures for the management of new media need to be fully implemented to maintain the public’s interests and national security.”[16]

Chen also increased the Communist Party’s presence in the community and private spaces to encourage state-sanctioned behavior. He deepened and expanded a 2009 party policy that trained a new generation of party members at a grassroots level. Between 2011 and 2015, more than 7,000 party cadres described as “outstanding” and members from the TAR were sent to 1,787 Tibetan Buddhist monasteries to expand party work and more than 20,000 Party members and cadres were sent to Tibetan villages and townships.[17] Additionally, in accordance with top-level instructions to ‘Sinicize’ Tibetan Buddhism (meaning to make it Chinese), Chen presided over a tightening of control over Buddhist reincarnation, as indicated in the publication of a database in 2016 of Tibetan lamas allowed to reincarnate with government permission.

As part of this methodology, Chen used re-education programs to enforce a correct way of thinking and living. Under his leadership in 2012, hundreds of Tibetans were systematically detained for re-education after returning from teachings by the Dalai Lama in India.[18] Many of the Tibetans detained following their return from India were charged daily fees of hundreds of yuan for their board during the ‘legal education’ process. Couples and families were separated while in detention, with some elderly people denied medication. A Tibetan from Lhasa who is now in exile said that the detentions “imposed unbearable psychological and financial pressure on families and communities.” Three years later, in 2015, Chen boasted that by then, “no one in the TAR had left the country to participate in religious teachings by the 14th Dalai Clique in foreign countries.”[19]

In addition to breaking ‘ethnic lineages and cultural roots,’ Chen also sought to build new political and social connections, such as through the enforced display of the Chinese flag and the promotion of marriages between Chinese and Tibetans for ‘ethnic mingling.’[20] His campaign to enforce the display of the Chinese flag (which is still emphasized today) created deep resentment and in 2013 led to the torture, imprisonment and deaths of Tibetans who refused to do so.[21] Preceding China’s National Day on Oct. 1, 2013, thousands of government officials and workers reportedly arrived in Driru (Chinese: Biru) in Nagchu (Chinese: Naqu) prefecture and set out to “force” all residents—monastic and lay—”to raise the Chinese national flag” above their homes.[22] Large numbers of People’s Armed Police (PAP) were deployed to the area, firing on unarmed protesters and beating and detaining many.[23] The situation in Driru remains tense today.

Security camera at the Barkhor, Lhasa, disguised as a prayer wheel. Photo used with the permission of the photographer.

Reinforcing assimilation with a system of surveillance, control and coercion

In securitizing ethnicity and framing Tibetan ethnicity and cultural identity as a threat to China’s national security, Chen sought to legitimize the use of extraordinary rule-breaking measures to manage the TAR. For example, to accelerate Tibetan assimilation and pre-empt protests and other unsanctioned expressions of Tibetan identity (religious, cultural or social), Chen rolled out a sophisticated and unprecedented network of surveillance and control designed to maintain stability in the TAR.[24] The network comprised two key instruments to instil fear and reinforce the assimilation project: 1) a militarized grid surveillance system and 2) coercive measures such as torture and collective punishment.

The militarized grid surveillance system

The militarized grid surveillance system was first tested in Beijing in 2004, before being rolled out in the TAR in 2011.[25] The militarized grid surveillance system is characterized by four features:

- “Convenience” police stations/checkpoints located 300-500 meters apart

- A neighborhood grid system that organizes neighborhoods into small units, each with a neighborhood committee and an integrated high-tech face-recognition surveillance system

- Locally recruited informants

- Party cadres stationed in monasteries

Within two months of assuming power in the TAR, Chen established hundreds of the surveillance posts he refers to as ‘convenience police stations.’ According to state media, between 2011 and 2015, the TAR established more than 698 24-hour police stations and checkpoints in seven cities and prefectures in the TAR.[26] In order to man them, the regional authorities dramatically increased recruitment. Between 2007 and the summer of 2011, the TAR advertised 2,830 positions for all types of police officers. After Chen took office, recruitment skyrocketed, according to research by scholars Adrian Zenz and James Leibold. Between the autumn of 2011 and 2016, the TAR advertised 12,313 policing-related positions—over four times as many as the preceding five years.[27]

Recruitment for security positions in the TAR increased four-fold under Chen Quanguo. (Source: Adrian Zenz and James Leibold (2017))

The police stations were reinforced by a neighborhood grid management system that was first introduced in urban parts of the TAR in April 2012. Designed to form “nets in the sky and traps on the ground,”[28] the grid system separated neighborhoods into three or more grid units. Each neighborhood unit has a committee responsible for gathering and recording information on the residents. All information gathered is used in a centrally coordinated system that collates human intelligence, face-recognition surveillance footage, and real-time big data analytics to monitor the local population and track “special groups.” Individuals who belong to the category of “special groups” include political prisoners, nuns and monks who are not resident in a Buddhist institution, former monks and nuns, Tibetans who have returned from the exile community in India, those under suspicion for loyalty to the Dalai Lama and people involved in earlier protests.[29]

The capacity and utility of big data analytics in real-time have advanced exponentially in Tibet. A report in the Chinese state media outlet Global Times highlighted a real-time big data system in Lhasa to “monitor tourism market dynamics.” It claimed the screens could display important events held in Tibet, ticket information and the number of tourists in different scenic spots, including the ability to “give a warning to the government on negative social events” and “guard against separatist forces.”[30]

New advancements in technology continue to expand the state’s surveillance capabilities, and subsequently change the security landscape in both the TAR and XUAR. More recently, the International Campaign for Tibet monitored the installation of QR codes on homes in a rural area of eastern Tibet, Kardze in Sichuan Province (the Tibetan area of Kham). State media reported that the codes, which can be scanned by officials on mobile devices in order to get instant access to the personal details of people living there, were installed in order to assist poverty alleviation—but that clearly fulfils the additional purpose of intensified surveillance.[31]

Following the installation of QR codes on the homes of the Uyghur Muslim community in order to get instant access to personal details of people living there, the same devices that can be scanned with smartphones by officials have now been imposed in rural areas of Kardze (Ganzi) in Sichuan, Tibet (Kham). This image from the official media shows the system being tested.

In addition to the neighborhood grid system, the militarized surveillance system also consists of locally recruited informants and party cadres stationed in monasteries and villages. The official state media detail specific instances of re-education and cultivating local informants near the border region to prevent Tibetans from escaping to India.[32] Similarly party cadres stationed in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and Tibetan villages and townships strengthen the surveillance system. As mentioned earlier, between 2011 and 2015, 7,000 party cadres were sent to monasteries, with more than 20,000 party members and cadres sent to villages and townships.[33] A party member in Shigatse prefecture, a Tibetan farmer in his 50s, gave a researcher this account of his work in Tibet: “The most difficult thing for me is that I have to give names and details of individuals who are politically suspicious, and who should be the target in my village in order to maintain social stability. If there are any political incidents in my village, county leaders would come with police and I have to tell them who is involved…Also I have to make sure that people do not spread any rumors about Dalai [Lama]…More recently, we party members have been told to monitor individuals’ daily activities—to see who is the most influenced by the Dalai, or who is dreaming of independence [Rangzen] and a return to the old Tibet. My responsibility is to make sure there is no chance of splittist activities in the village and to lead villagers in the right political direction.”[34]

The prevalence of the sophisticated security architecture has been widely felt, including in eastern Tibetan areas of Kham and Amdo (areas outside the TAR). Sources report to the International Campaign to Tibet what appears to be almost a “normalization” of repression. A recent visitor to eastern areas of the plateau said: “It is impossible to visit Tibet without experiencing the intrusive levels of surveillance and security as an indelible imprint. It is disturbing to see how measures like security cameras everywhere, including in the most remote monasteries and in the vast grasslands, are now almost accepted, normalized; the psychological impacts are untold and must be devastating. Fear is ever-present.”

Coercive measures: Torture and collective punishment

Chen’s security architecture has also relied on the use of torture and collective punishment to deter Tibetans from engaging in nonviolent forms of expression, dissent or information sharing. Numerous cases of torture were reported following the March 2008 protests that spread across the TAR and neighboring regions of eastern Tibet. Sadly, the practice of torture continued under Chen’s rule, and in particular, expanded into neighboring areas of eastern Tibet. A 2015 special report by the International Campaign for Tibet documented 29 cases of torture and recorded at least three known cases of torture under Chen’s tenure in the TAR. Ngawang Jampel (also known as Ngawang Jamyang), a senior Tibetan monk and Buddhist scholar, died in custody after one month, while Namgyal Tseltrim lost the use of his right hand after nearly eight months of detention without charges. The special report found the level of violence directed at Tibetan political prisoners is frequently extreme and results in severe scars, paralysis, loss of limbs, organ damage and serious psychological trauma.[35] Their psychological suffering is heightened by the knowledge that their family and friends are also under government scrutiny.

Collective punishment, the act of targeting one’s family, friends and community members, is an equally effective tool for coercion and deterrence. During Chen’s tenure in the TAR, self-immolation was criminalized. The December 2012 Opinion on handling cases of self-immolation in Tibetan areas according to Law not only criminalized self-immolators, but also individuals intending to self-immolate and individuals suspected of influencing or assisting self-immolators.[36] As noted earlier, the distribution of state secrets or information concerning national security was also criminalized, allowing the state to charge individuals who shared footage or information relating to self-immolations or other information.[37] This was observed in practice in January 2013 when Lobsang Konchok, a monk from Kirti Monastery, was sentenced to “death with a two-year reprieve” and his nephew sentenced to 10 years in prison for committing “intentional homicide” for “inciting and coercing eight people to self-immolate, resulting in three deaths.”[38] As noted in a 2015 South China Morning Post article about the decline in self-immolations, one monk explained “Many monks don’t want to endanger their families.”[39] In addition, in April 2013, a court in Malho (Chinese: Huangnan) Tibet Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai sentenced four men to six year in prison for sharing information on Tibetan self-immolations with “separatist organizations” outside China.[40]

This image shows the capability of facial recognition technology by Hikvision CCTV company to recognize ‘ethnic minorities’. Hikvision demonstrated their AI cloud system of ‘minority analytics’ at a company summit on March 30, 2018, in Hangzhou, China.

Conclusion

The Chinese state’s model of repression in Xinjiang was devised under the leadership of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Party Secretary Chen Quanguo. His strategy and policy for managing China’s ethnic issues has its roots in the Tibetan Autonomous Region—his previous post and the base where he tested and perfected a policy of securitizing ethnic identity. In framing ethnic (Tibetan and later Uyghur) identity as a threat to national security, Chen pursued a two-pronged approach to manage the threat of ethnic identity: He launched a campaign to accelerate assimilation by ‘breaking ethnic lineages and cultural roots,’ and he built a sophisticated and coercive security architecture to enforce assimilation. Chen’s strategy to isolate Tibetans from the outside world, sow distrust and fear in communities, and enforce a state version of acceptable Tibetan life received positive recognition and was deemed politically capable and reliable enough for Chen to take on the difficult position of party secretary for the XUAR.[41] While differences in religious roots and transnational links will shape different manifestations of state repression in Tibet and Xinjiang, Chen’s model of repression retains the same underlying features of wide-scale ethnic discrimination and enforced assimilation backed by a sophisticated security architecture. On a more general level, the status of Chen’s strategy as a model of governance presents a serious challenge for Tibetans, Uyghurs and Chinese citizens who wish to express their cultural identities free from state interference. The international community should thus be alerted and must push back in a robust manner against the Chinese government.

Footnotes:

[1] Frequently referred to as East Turkestan by Uyghurs.

[2] See for example, Human Rights Watch, ‘China: Massive Crackdown in Muslim Region’, September 9, 2018.

[3] See CERD Concluding Observations , August 30, 2018, CERD/C/CHN/CO/14-17, p. 7.

[4] Reuters, ‘Exclusive: In rare coordinated move, Western envoys seek meeting on Xinjiang concerns’, November 15, 2018

[5] Adrian Zenz and James Leibold, 21 September 2017, ‘Chen Quanguo: The Strongman Behind Beijing’s Securitisation Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang’, The Jamestown Foundation: China Brief, https://jamestown.org/program/chen-quanguo-the-strongman-behind-beijings-securitization-strategy-in-tibet-and-xinjiang/.

[6] For a conceptualization of ‘Securitization’ see Rens van Munster, 26 June 2012, ‘Securitisation’, Oxford Bibliographies, http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199743292/obo-9780199743292-0091.xml.

[7] According to official documents, the purpose of the re-education camps in Xinjiang is to “break [Uighur] lineage, break their roots, break their connections, and break their origins.” Cited in ‘Tear gas, tasers and textbooks: Inside China’s Xinjiang internment camps’, October 24, 2018, by Ben Dooley, https://www.hongkongfp.com/2018/10/24/tear-gas-tasers-textbooks-inside-chinas-xinjiang-internment-camps/

[8] See ‘China Vitae’, Chen Quanguo, http://www.chinavitae.com/biography/Chen_Quanguo (accessed on November 29, 2018)

[9] See in James Leibold, ‘Hu the Uniter: Hu Lianhe and the Radical Turn in China’s Xinjiang Policy’, Jamestown Foundation, China Brief Volume: 18 Issue: 16

[10] See in James Leibold, ‘Ethnic policy in China: is reform inevitable?’, East-West-Center Policy Studies, No. 68 (2013)

[11] International Campaign for Tibet report, ‘Storm in the Grasslands’, p 48, https://www.https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/storminthegrassland-FINAL-HR.pdf

[12] People’s Daily, August 10, 2015, in Chinese: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2015/0810/c397848-27436329.html

[13] Cited by Albawaba news portal, September 4, 2018, ‘Chen Quanguo: The Man Who Silenced Tibet Is Perfecting a Police State in Xinjiang, China’, https://www.albawaba.com/news/chen-quanguo-man-who-silenced-tibet-perfecting-police-state-xinjiang-china-1181388

[14] Cited in International Campaign for Tibet report, ‘Storm in the Grasslands: Self-immolations in Tibet and Chinese policy’, https://www.https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/storminthegrassland-FINAL-HR.pdf

[15] 21 August 2012, ‘Senior monk sentenced to 7 years for sharing information, Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, http://tchrd.org/senior-monk-sentenced-to-7-years-for-sharing-information-2/.

[16] Sui-Lee Wee, 1 March 2012, ‘China’s top Tibet official orders tighter control of Internet’, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-tibet/chinas-top-tibet-official-orders-tighter-control-of-internet-idUSTRE8200BZ20120301.

[17] People’s Daily Online, August 10, 2015, http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2015/0810/c397848-27436329.html

[18] International Campaign for Tibet report, ‘Lockdown in Lhasa at Tibetan New Year; unprecedented detentions of hundreds of Tibetans after Dalai Lama teaching in exile’, February 22, 2012, https://www.https://savetibet.org/lockdown-in-lhasa-at-tibetan-new-year-unprecedented-detentions-of-hundreds-of-tibetans-after-dalai-lama-teaching-in-exile/

[19] China Tibet Net by Wu Jianying (in Chinese), October 11, 2015, http://www.tibet.cn/news/focus/14471159145.shtml

[20] International Campaign for Tibet report, ‘Chinese Party official promotes inter-racial marriages in Tibet to create “unity”’, August 28, 2014, https://www.https://savetibet.org/chinese-party-official-promotes-inter-racial-marriages-in-tibet-to-create-unity/

[21] See Wu Qiang, in: China Change, August 12, 2014 ‘Urban Grid Management and Police State in China: A Brief Overview.

[22] Radio Free Asia, October 2, 2013

[23] Congressional-Executive Commission on China Special Report, November 20, 2013, ‘Biru Villagers Respond With Protests to Chinese Flags, Security, Detentions’, https://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/Biru%20County%20Crackdown_20nov13.pdf. Also see International Campaign for Tibet report, October 15, 2013, ‘New images of deepening crackdown in Nagchu, Tibet’, https://www.https://savetibet.org/new-images-of-deepening-crackdown-in-nagchu-tibet/

[24] January, 2012, cited in Human Rights Watch, ‘China: Alarming New Surveillance, Security in Tibet’, March 20, 2013, https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/03/20/china-alarming-new-surveillance-security-tibet

[26] People’s Daily, August 10, 2015, in Chinese: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2015/0810/c397848-27436329.html

[27] Adrian Zenz and James Leibold, 21 September 2017, ‘Chen Quanguo: The Strongman Behind Beijing’s Securitization Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang’, China Brief, Vol. 17, Issue 12, Jamestown Foundation, https://jamestown.org/program/chen-quanguo-the-strongman-behind-beijings-securitization-strategy-in-tibet-and-xinjiang/.

[28] (Tibetan: dra ba, Chinese: wangge). On February 14, 2013, Yu Zhengsheng, Standing Committee member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and the top official in China in charge of nationality policy, confirmed that the system should be put into effect throughout the region to form “nets in the sky and traps on the ground,” an indication that the system is primarily designed for surveillance and control. Cited by Human Rights Watch, ibid.

[29] Based on translation of an official notice, Human Rights Watch reported: “These ‘special groups’ appear to be the ‘critical sectors,’ or ‘key persons’ in the TAR, the control of whom is described in official documents as the most important task or objective of stability maintenance work in Tibet, second only to establishing teams of [Party] cadres in villages and monasteries. Human Rights Watch report, ibid. According to the same report, cities and towns in China are divided into sub-districts, earlier called “street offices” (Tib.: khrom gzhung don gchod khang, Ch.: jiedao banshichu), township-level administrations run by government officials. The sub-districts are further divided into “neighborhoods,” renamed “communities” (Tib.: sde khul, Ch.: shequ) since 1999, managed by semi-official “mass organizations” known as “neighborhood committees” or “residents’ committees” (Tib.: sa gnas u yon lhan khang, Ch.: jumin weiyuanhui).

[30] Global Times, ‘Big data system keeping track of visitor information helps Tibet’s tourism’, October 3, 2018, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1121655.shtml

[31] This is the first such reference from Tibet tracked by ICT, although QR codes may have been installed in other areas of Tibet too. China Tibet Online, ‘Mobile Internet facilitates village work’, November 9, 2018.

[32] People’s Daily Online, August 10, 2015, http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2015/0810/c397848-27436329.html.

[33] People’s Daily Online, August 10, 2015, http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2015/0810/c397848-27436329.html.

[34] Cited in International Campaign for Tibet report, ‘Storm in the Grasslands: Self-immolations in Tibet and Chinese policy’, https://www.https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/storminthegrassland-FINAL-HR.pdf

[35] International Campaign for Tibet Special Report, February 26, 2015, ‘Torture and impunity: 29 cases of Tibetan political prisoners (2008-2014)’, International campaign for Tibet, https://www.https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/torture-and-impunity-A4.pdf.

[36] International Campaign for Tibet report, ‘Acts of Significant Evil: The criminalization of self-immolations’, https://www.https://savetibet.org/acts-of-significant-evil-report/ and U.S. Department of State, 28 July 2014, ‘2013 Report on International Religious Freedom: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macao) – Tibet’, https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2013/eap/222125.htm.

[37] Sui-Lee Wee, 1 March 2012, ‘China’s top Tibet official orders tighter control of Internet’, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-tibet/chinas-top-tibet-official-orders-tighter-control-of-internet-idUSTRE8200BZ20120301.

[38] https://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/01/world/asia/chinese-court-issues-severe-sentences-in-tibetan-self-immolations.html

[39] ‘Tibetan monks shy away from self-immolation as families threatened by Chinese police’, 22 December 2015, South China Morning Post, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/1893884/tibetan-monks-shy-away-self-immolation-families.

[40] Human Rights Watch, May 2016, ‘Appendix III: Tibetan Political Detainees, 2013-2015’, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/tibet0516web_appendixiii.pdf, page 5.

[41] Adrian Zenz and James Leibold, 21 September 2017, ‘Chen Quanguo: The Strongman Behind Beijing’s Securitization Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang’, China Brief, Vol. 17, Issue. 12, Jamestown Foundation, https://jamestown.org/program/chen-quanguo-the-strongman-behind-beijings-securitization-strategy-in-tibet-and-xinjiang/.