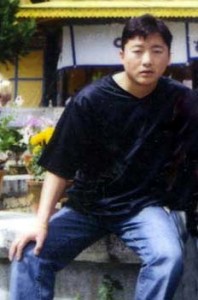

Twenty-eight year old Tendar’s death following torture after his arrest for trying to help an elderly monk was featured in a video released by the Tibetan government in exile in March. (Phayul.com)

This report gives details of the deaths of two Tibetans in different areas of Tibet as a result of being subjected to excessive brutality in custody. These are not isolated incidents; many other deaths following torture have occurred, but full details are often not known.

The account of 28-year old Tendar’s death reached the outside world after the Tibetan government in exile made a video available which featured disturbing images of his body after torture. There are now fears for the safety of his step-father after news of the death became known. His mother is reportedly under close police surveillance. Tendar was taken into custody on March 14, 2008, after he tried to help an elderly monk who was being beaten by police.

In a separate incident, Paltsal Kyab, a 45-year old nomad, died in May, 2008, after being taken into police custody following a protest in his hometown on March 17, 2008. Paltsal Kyab, who left five children, had told protestors not to burn any buildings and to follow the non-violent path. But he was taken into custody and died after brutal beatings in detention.

A Tibetan writer referred to Paltsal Kyab’s death in a collection of writings called Eastern Snow Mountain that was banned immediately after publication: “To say that someone has been beaten to death, isn’t this something that should never have to be said in this day and age? To say that someone has been beaten to death is something that recalls the terror of the “Democratic Reform” era [of the late 1950s/ early ’60s].”

The killing of Tendar

Twenty-eight year old Tendar’s death following torture after his arrest for trying to help an elderly monk was featured in a video released by the Tibetan government in exile in March. A Tibetan blogger writing in Chinese described the images as follows: “One of his legs was cut with many bloody knife wounds and a nail had been driven in to a toenail on his right foot. A great deal of flesh had been cut away from his bottom, where the wound was rotting and infested with insects. Where his waist had been beaten with electric batons, the flesh had started to decay. There were many wounds on his back and on his face. One of the wounds was covered with transparent tape. Because he had not received any medical care, he was already on the verge of death.”

The Chinese government reacted strongly to the release of the video, blocking Youtube for a period after it was publicized internationally, and stating that the “Dalai group fabricates information about Tibet”. (‘Lhasa riot footage ‘has been doctored’, China Daily, March 27, 2009). China’s response to the video ensured that more people knew about Tendar’s death, although full details have not been made public until now. The account below is compiled using testimony from several sources. There are now fears for the welfare of Tendar’s retired step-father, who is in his early sixties, since news of the death reached the outside world.

Tendar worked in the customer services department of a Chinese telecommunications company and lived in Lhasa. On March 14, when Tibetan protests turned violent on the streets of Lhasa, Tendar witnessed an elderly monk being beaten by Chinese security personnel. Although details of what happened are sketchy, according to reports by Tibetans who know Tendar, and others in Lhasa on that day, it seems that Tendar tried to help the monk, by telling the police to have mercy on him. He did so at a time that armed police were opening fire on the rioters. Tendar was shot and fell to the ground. Still conscious, he was taken away by police. A Tibetan source who was in Lhasa after the incident and spoke to Tibetans who know Tendar said: “The injury didn’t appear to be life-threatening. I was told that he was taken to the Lhasa General Hospital that is run by the People’s Liberation Army. While he was at the hospital, a team of four to five Chinese security personnel visited him every four to six hours. During those times they took turns in beating him while interrogating him about his involvement [in the March 14 protests]. They were using iron rods and cigarette butts to burn his skin. He was tortured repeatedly and his condition deteriorated rapidly.”

At this time, none of Tendar’s family or friends knew where he was, a pattern consistent with the wave of disappearances that took place after March 14, and that is still occurring in some areas. Through connections, Tendar’s family managed to locate him. When they were allowed to visit, he was “in shock, and in excruciating pain. Every movement of his body would cause him to scream with pain”, said the same Tibetan source. He was unable to walk and his body appeared to be paralysed from the waist down. Tendar said that he had witnessed a Tibetan monk at the hospital being beaten to death with iron bars by security personnel. He begged to be taken home.

The same Tibetan source said: “While at hospital, Tendar had tried to kill himself twice by jumping off the window from his room. He had managed to drag his body to the window but was unable to get out as he could not move the lower part of his body.”

The Tibetan source believes that Tendar was only released to his family as the authorities knew there was no hope of his recovery. This is consistent with other cases where Tibetans have died after torture; the authorities seek to avoid being responsible for a person’s death while they are under their charge. His relatives attempted to get medical care for him but hospitals were reluctant to take him into their care due to the political sensitivity of a patient who had been involved on March 14. Tendar was finally admitted to the Peoples’ Hospital near the Potala Palace, where he was immediately taken into intensive care. The Tibetan source said: “Some of the nursing staff had tears in their eyes when they saw the serious nature of his injuries.”

Tendar spent 20 days in hospital and his condition continued to deteriorate. He became unconscious, and medical staff told his family that there was nothing more they could do for him. Tendar’s family had to pay a medical bill of 90,000 yuan ($13,000) before they could take him home.

Tendar died at home 13 days later, on June 19, 2008. Video footage obtained by the Tibetan government in exile depicts vultures at his sky burial site at Toelung, west of Lhasa. The same Tibetan source, who is no longer in Tibet but who spoke to eyewitnesses, said: “One could see on his body the marks of iron rods. His body was nothing but bone and skin. When his body was being prepared for the vultures [a ritual called Jhador in Tibetan], a slender metal bar or long nail about one-third of a meter in length was found inserted through the bottom of his leg. This appeared to be one of the torture instruments used during interrogation.”

The story of Tendar’s death is well-known in Lhasa and has even been written about by Tibetan bloggers in Chinese. Many people who did not know Tendar but who had heard about him came to mark his death at important dates afterwards. “Those who were fearful of attending these occasions due to being seen by security personnel sent money and khatags [white Tibetan blessing scarves],” said the same source.

A Tibetan writer said: “Several hundred Tibetans came to his funeral services. Many came out of deep sympathy for a stranger who suffered a terrible tragedy. At the funeral service, the mother of this youth said sadly, ‘I cry not only for my son who died a tragic death, I cry even more for those sons who are being tortured. As a mother, I can’t imagine the torments and suffering my son endured in prison.'”

According to different Tibetan sources, there are a number of cases over the past year where Tibetans were initially injured by either gunfire or beatings while being taken into custody. Although these initial injuries did not appear to be life-threatening, torture following detention has in these cases led to dramatic deterioration and death. Tibetans taken into custody with bullet wounds after March 14, 2008, were rarely given medical treatment according to sources. According to anecdotal reports from Lhasa, the worst torture was carried out by People’s Liberation Army and People’s Armed Police troops brought in from outside the city.

The death of Paltsal Kyab after torture

“Shikalo [Jakpalo] a man in his forties from Charo Xiang in Ngaba county, was beaten to death on false charges. His precious life has fizzled out. This father and cornerstone of his household leaves behind him a widow and [five] orphans, weeping inside. This life-demeaning disaster has ruined life for one household.”

– Extract from The Eastern Snow Mountain (Shar Dungri), a collection of writings from the Tibetan area of Amdo that is the only known material in Tibetan on the 2008 protests to have been published in the PRC.

On May 26, 2008, two local township leaders in Charo township, Ngaba (Chinese: Aba), Sichuan (the Tibetan area of Amdo) came to tell the family of 45-year old nomad Paltsal Kyab, also known as Jakpalo, that he was dead. Although officials said that he had died “of natural causes” while being held in custody following a protest in the area on March 17, 2008, when the body was released to the family there were clear signs of torture and brutal beatings.

Paltsal Kyab’s younger brother, Kalsang, who now lives in exile, told ICT that according to witnesses who saw his body, “The whole front of his body was completely bruised blue and covered with blisters from burns. His whole back was also covered in bruises, and there was not even a tiny spot of natural skin tone on his back and front torso. His arms were also severely bruised with clumps of hardened blood.”

Paltsal Kyab, who was married with five children, was taken into custody following a peaceful demonstration that occurred in Charo on March 17, 2008. According to anecdotal accounts from the area given to Paltsal Kyab’s brother, around 100 young Tibetans held a protest on the main street “because they believed that the United Nations and foreign media chose not to listen to and see the truth in Tibet.” The Tibetans began to talk about burning a building down. According to his brother, Paltsal Kyab told the Tibetans that it was important not to take this action, saying: “We Tibetans must follow His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s non-violent path. Our only weapon is our truth. The building belongs to the government, but several Tibetan and Chinese families are living in there.” At least three people in a building nearby testified to police that Paltsal Kyab had persuaded the Tibetans not to be violent, according to Kalsang.

After the incident, according to his friends, Paltsal talked about going to the police station to tell officers that he had not committed any violation such as destroying buildings or cars, or harming anyone. But he heard from his friends that his name was already on the wanted list, and that individuals who were detained were being badly beaten. Paltsal went to see a relative who was ill out of town.

On April 9 last year, at around midnight, 11 police raided Paltsal’s home, while a truckload of armed soldiers waited outside. According to reports from the family, one police officer pointed a gun at the head of Paltsal’s 14 year old son and asked him where his father was. His son replied that his father had gone to see his relative who was ill. Paltsal’s wife was then dragged out of her room and asked the same question. She gave the same answer as her son, but gave a different name of the relative. Because they had given different names, the police claimed that they were lying, and Paltsal’s son was taken into custody. On arrival at the police station the teenager was slapped, kicked and punched for hours during interrogation. He was released the next day.

When Paltsal was told about his son, he came home immediately. Kalsang said: “Our family had heard that the Chinese government says that people involved in protest must surrender voluntarily and that people who did so would be treated leniently, as opposed to people who are seized by police. Paltsal’s relatives told him that he was a father of five children so that it wouldn’t be possible for him to hide from police throughout his life. Paltsal also knew that his son had been beaten and interrogated. So he decided to surrender voluntarily.”

On April 17 or 18, 2008, Paltsal went to the local police station and gave himself up. He was held there for two weeks and then transferred to a detention center in Ngaba on April 27, 2008. The family heard nothing about his condition or whereabouts until May 26, 2008, when two local township leaders came to Paltsal’s home to inform his wife and children of his death.

Paltsal’s family members were allowed to collect his body from the detention center. Kalsang says: “Upon arrival, the relatives were told by the Ngaba police that the cause of his death was sickness, not torture. They also allegedly claimed that they had taken him to a hospital twice because of his kidney and stomach problems. But his relatives said that when Paltsal went to the police station to surrender he was a normal healthy man with no history of any major health problems. The police officers never acknowledged the cause of death as torture but they immediately started to offer money to the family. The family was not allowed to take photos of his body or tell anyone anything about what had happened.”

Kalsang said that he was later informed by various sources that his elder brother had been very badly tortured in custody. Family members asked for permission to take his body to Kirti monastery in Ngaba. It is important in Tibetan culture for prayers to be said for a person immediately after his death in order to help ensure a peaceful transition. But the army refused permission. Kalsang said: “They even could not take Paltsal’s body to Kirti monastery to pray for Paltsal’s soul.”

Paltsal was given a traditional sky burial, with police officers present, including two senior Tibetan police officers. Kalsang said: “It was obvious from the condition of Paltsal’s body that he had suffered an agonizing and painful death due to severe torture, not of natural causes.” Those preparing his body for burial, which involves dismemberment, told the family that there was severe damage to his internal organs, including his small intestines, gall-bladder and kidneys.

A Tibetan writer from Ngaba, the Tibetan area of Amdo, wrote anonymously about Paltsal’s death in a collection of writings called Shar Dungri, or Eastern Snow Mountain. The article, entitled, ‘What human rights do we have over our bodies?’ was written by a writer who calls himself Nyen, ‘The Wild One’, from Sichuan. He writes: “To say that someone has been beaten to death, isn’t this something that should never have to be said in this day and age? To say that someone has been beaten to death is something that recalls the terror of the ‘Democratic Reform’ era [of the late ’50s/ early ’60s]. Generally speaking, no-one enjoys ‘vengeance’ or continuing ‘old feuds’. But for the young generation, the murder of their father leaves an impression that cannot be forgotten as long as they live. That is the certain outcome of repression, beating and killing. We have no wish for ‘revenge’ or ‘feuds’. We call for reaching a time in which the younger generation will have no ‘revenge’ to seek or ‘feuds’ to settle. The young generation has not come into this world for revenge or to settle feuds, but to see the spectacle of a brighter tomorrow, to seek refuge in a place enjoying the bright spring of freedom, democracy and equality.” (Translated into English by ICT. The full article is published in the report ‘A Great Mountain Burned by Fire: China’s Crackdown in Tibet‘).