TORTURE AND IMPUNITY

29 CASES OF TIBETAN POLITICAL PRISONERS

TORTURE AND IMPUNITY

29 CASES OF TIBETAN POLITICAL PRISONERS

He “simply folded his hands and died.”

Sources from Tibet close to 43-year old Goshul Lobsang, who never recovered from injuries due to torture and malnourishment in prison and who died at home in March 2014, soon after his release.

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report documents a pattern of torture and mistreatment of Tibetans through an investigation into cases of recently released prisoners, including details of 14 Tibetans who have died as a consequence. The report concludes that although the PRC officially prohibits torture, it has become endemic in Tibet, a result both of a political emphasis on ensuring ‘stability’ and a culture of impunity among officials, paramilitary troops and security personnel.

Since the unrest in 2008 and crackdown in Tibet, the Chinese authorities have adopted a harsher approach to suppressing dissent and there has been a significant spike in the number of Tibetan political prisoners taken in Tibetan areas of the PRC. There is also evidence that since 2008 torture has become more widespread and directed at a broader sector of society.

A younger generation of Tibetans is paying a high price with their lives for peaceful expression of views in a political climate in which almost any expression of Tibetan identity not directly sanctioned by the state can be characterized as ‘reactionary’ or ‘splittist’, and therefore ‘criminal’. But even despite the intensified dangers, Tibetans are continuing to take bold steps in asserting their national identity and defending their culture.

This report details specific cases of 29 Tibetans, of whom 14 died as a result of torture. The report also details the impact of imprisonment – whether extra-judicial, interrogation or a formal sentence – on the lives of Tibetan political prisoners released over the past two years whose ordeals have become known to the outside world, despite rigorous controls on information flow.

Despite Chinese official assertions that China’s legislative, administrative, and judicial departments have adopted measures against torture, there are no indications of investigations into allegations of torture and mistreatment, let alone into cases of Tibetans who have been subjected to arbitrary detentions. Financial aid or compensation for injuries suffered during detention is extremely rare. Provided there is an – albeit limited – debate about cases of torture in the PRC outside of Tibet, the complete silence on such cases in Tibet contributes to the discriminatory policies and the lawlessness persisting in Tibet.

“I cry not only for my son who died a tragic death, I cry even more for those sons who are being tortured. As a mother, I can’t imagine the torments and suffering my son endured in prison.”

– The mother of Tendar, a Tibetan man in his late twenties, who died as a result of torture after being detained trying to help an elderly monk.[1]

CONCERNS

The International Campaign for Tibet (ICT) is deeply concerned about the spike in political imprisonment and the widespread use of torture on Tibetans, in contravention of both Chinese and international law. Torture represents a serious violation of fundamental human rights, and its use must be prohibited, publicly condemned, with its victims compensated and those responsible brought to justice.

The use of torture has not only an immediate impact on its victims, but also on the entire Tibetan society. It deepens Tibetan resentment against state power and deepens the sense of oppression by the Chinese authorities. It appears to have become common knowledge among Tibetans that they will be subjected to torture when taken into custody, particularly after being involved in political protest. In August 2014, a young Tibetan committed suicide while under detention; according to sources, he killed himself in protest against the torture by the Chinese authorities.[2]

For many Tibetans, it appears to be of utmost importance that accounts of torture and mistreatment are known outside Tibet. Before he died following torture and malnourishment in prison, 43-year old Goshul Lobsang expressed his wish for a blessing from the Dalai Lama, and also said that he wanted to let the outside world know about the lives of Tibetan political prisoners under Chinese oppression. He passed away in March 2014; Tibetan sources said that: “[At the end] he could not say anything, but simply folded his hands and died.”

“The whole front of his body was completely bruised blue and covered with blisters from burns. His whole back was also covered in bruises, and there was not even a tiny spot of natural skin tone on his back and front torso. His arms were also severely bruised with clumps of hardened blood.”

– The brother of a torture victim cites witnesses of his brother’s ordeal.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The International Campaign for Tibet urges the People’s Republic of China to:

- conduct an inquiry into the cases of custodial deaths and extra-judicial killings detailed in this report and bring those responsible to justice.

- investigate thoroughly reports of torture and mistreatment in detention and also bring those responsible to justice, pursuant to Chinese law, the People’s Republic of China’s obligations under the Convention against Torture, of which it is a state Party,[3] and a rule of international law that nobody is allowed to participate in torture.[4]

- given that the Criminal Procedure Law in China now provides that any confessions collected from a detainee by illegal means, such as torture, shall be excluded from all stages of the criminal justice process, ICT strongly encourages efforts to ensure that the revised Criminal Procedure Law is effectively implemented and monitored so that these welcome revisions take full effect.[5]

- enforce Article 18 of the People’s Police Law of the People’s Republic of China which obligates all Chinese police to “exercise their functions and powers respectively in accordance with the provisions of relevant laws and administrative rules and regulations.”

- enforce Articles 7 and 14 of the Prison Law of the People’s Republic of China which stipulate that guards cannot humiliate detainees or violate their personal safety, use torture or corporal punishment, ”beat or connive at others to beat a prisoner,” or “humiliate the human dignity of a prisoner.”

- release all Tibetan prisoners who have been detained for religious beliefs or practices, or peaceful expression of views.

- address the underlying grievances of Tibetans by respecting their universal rights and by entering into meaningful negotiations with the Tibetans.

- safeguard principles of due process according to international law, including the right to access to legal representation of choice and adequate medical treatment, as specified in China’s Criminal Law.

- publicly condemn cases of torture and mistreatment in Tibet, in order to counter the culture of impunity persisting in Tibet.

- render compensation to victims of torture, or in case of deceased prisoners, compensation to their families and relatives.

- introduce self-sustaining social and political institutions including: a free and investigatory press, citizen-based independent human rights monitoring organizations, independent commissions visiting places of detention, and independent, fair and accessible courts and prosecutors.

The International Campaign for Tibet urges the international community, concerned governments, parliaments and United Nations institutions:

- to call for the immediate release of all those Tibetans who have been detained and sentenced for peaceful expression of views or non-violent dissent.

- to call for an investigation into the cases of Tibetans who died as a result of torture in custody.

- to challenge the government of the People’s Republic of China on its contraventions of international law implicit in widespread torture of detainees.

- to urge the government of the People’s Republic of China to safeguard minimum standards for due process and judicial rights of those detained or are subject to penal investigation.

- to urge for adequate and if necessary immediate medical treatment for those Tibetans who have suffered from torture, as detailed in this report, in particular.

- to use bilateral and international fora such as human rights dialogues to urge the Chinese government to comply with national and international standards with regard to torture and mistreatment.

- to examine the fifth periodic report of the People’s Republic of China at the Committee Against Torture (CAT/C/CHN/5) and to address concerns and recommendations to the People’s Republic of China; in particular the Committee Against Torture should include concerns and recommendations with regard to the use of torture in Tibet in its “concluding observations.”

The International Campaign for Tibet asks Chinese human rights activists, academics, journalist and other activists:

- to give special attention to the specific discriminatory policies in Tibet and to include it into their activism.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lhasa’s unique and precious remaining cultural heritage, due to be discussed at the upcoming UNESCO meeting in Bahrain (opening June 24), is imperiled as China fails to uphold its responsibilities provided by the World Heritage Convention and UNESCO guidelines.

Since the iconic Potala Palace and other significant buildings were recognized as UNESCO World Heritage in 1994, 2000, and 2001, termed by UNESCO as the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’, dozens of historic buildings have been demolished in Tibet’s ancient capital and the cityscape transformed by rapid urbanisation and infrastructure construction in accordance with China’s strategic and economic objectives. Four months on from a major fire at the holy Jokhang Temple in the heart of the city, the Chinese government is still blocking access and information and may be covering up substantial damage with inappropriate repair work.

The UNESCO World Heritage Committee, at its upcoming session in Manama, Bahrain (June 24-July 4), is to vote on a draft decision which requests information about the state of conservation of the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ and of its surroundings, the so- called “buffer zones”, “as soon as possible”.[1] The draft decision also requests more detailed reports about the damage at the Jokhang temple and seeks an invitation for a ‘Reactive Monitoring Mission’ to assess the damage and repair work at the temple.

Bhuchung Tsering, Vice President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: “Lhasa – the name means ‘Place of the Gods’ – was the center of Tibetan Buddhism, a city of pilgrimage, a cosmopolitan locus of Tibetan civilization, language and culture. In a travesty of conservation, ancient buildings have been demolished and ‘reconstructed’ as fakes – characterized by China as ‘authentic replicas’ – and emblematic of the commercialization of Tibetan culture. The need for protection of Lhasa’s remaining heritage, particularly following the fire at the Jokhang Temple, is now urgent. The Tibetan people have a right to enjoyment and protection of their cultural heritage. The Chinese government is failing to uphold this right.”

“UNESCO must be vigilant in enforcing the World Heritage Convention and take serious measures for the protection of Lhasa’s remaining cultural heritage. As the United Nations body tasked with the protection of the world’s irreplaceable natural and cultural wonders, at the meeting in Bahrain the UNESCO World Heritage Committee must act in accordance with its mandate, and should seriously question the urban plans imposed by a government that has already destroyed many historic buildings. UNESCO should require the Chinese government to adopt an authentic conservation approach in order for the remaining fragments of old Lhasa to be preserved, based on a detailed plan to protect the historic Barkhor area and buildings in the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’.

“Importantly, the Committee and member states of the world’s leading heritage organisation should ensure urgent access for independent verification of the status of the unique and precious architecture of the Jokhang temple, and its statues and murals, with a view to ensuring that repair work is conducted under the supervision of accredited conservation experts.”

THIS INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGN FOR TIBET REPORT DETAILS THE FOLLOWING

- The Chinese government claims that it is developing Lhasa as a “green and harmonious city”, but images and urban plans included with this report convey the scale of new development and destruction since the historic center gained World Heritage status from 1994 onwards. Chinese officials say that “maintaining social stability”, a political term meaning the repression of any form of dissent, is a precondition for Lhasa’s development.

- Images included with this report show the massive expansion and transformation of Lhasa, including infrastructure projects with roads intended to be wide enough to serve as runways for military planes in line with the Chinese government’s focus on security and militarization, dramatic expansion of the new town near Lhasa’s main railway station and high rise development in the lower Toelung valley area.

- Dozens of historic buildings were demolished in the 10 years before the Jokhang Temple was listed under UNESCO in 2000, many of them with UNESCO World Heritage status. The ancient circumambulation route known as the Lingkor, which takes pilgrims around a number of holy sites in Lhasa, has been disrupted by often impassable new roads and Chinese buildings.

- After a major fire at the Jokhang Temple, the sacred heart of Lhasa, in February, China continues to suppress information about the extent of the damage and block Tibetans from circulating news. Active engagement or promotion of heritage issues by Tibetans in Lhasa today can be dangerous, given the political climate of total surveillance and hyper-securitization, in which peaceful expression of views about Tibetan culture, identity or religion can be criminalized. No foreign journalists or heritage experts have been allowed to visit Lhasa to ascertain the situation although the Chinese authorities acknowledged to UNESCO, a month after the event, that damage to the Jokhang is extensive.

- In a response to UNESCO late last year on the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ in Lhasa, the Chinese authorities did not mention the key issue of preservation of historic buildings. And in its submissions on Lhasa, the World Heritage Committee too does not outline specific recommendations to protect the historic Barkhor and its surroundings. Almost all of the historic buildings of old Lhasa, once the center of Tibetan Buddhism and with a pivotal role in Tibetan civilization, have been destroyed and replaced by fake ‘Tibetan’-style architecture, which is completely at odds with its UNESCO World Heritage responsibilities. Official Chinese planning documents obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet confirm that this is set to continue with the remaining historic buildings, which number around 50 as new construction continues at a staggering rate.

- The acute threat to the integrity of the UNESCO World Heritage ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ is linked to a dramatic increase in Chinese domestic tourism and a rapidly expanding infrastructure in which Lhasa is a center of a new network of roads, railways and airports with dual military and civilian use, reflecting the region’s strategic significance to the Chinese government. Official planning documents reveal that development and tourism in the interests of the ideological imperative of “harmonious socialism” are the key priorities, with conservation scarcely mentioned.

2. NOTE ON METHODOLOGY

In this report, ICT sought to document (i) a range of cases where there was a clear correlation of death with torture, and (ii) Tibetan political prisoners whose cases are relatively well-known in Tibet and who have been released in 2013-14 and who have suffered from torture and mistreatment.

The report covers cases of 29 Tibetan political prisoners from 2008 – a year of widespread protest in Tibet – to 2014, primarily focusing on cases of individuals who have died as a result of torture between 2008 and 2014 or were released in 2013-14.

The report does not seek to be exhaustive or give a comprehensive account of all Tibetans who have died in custody or following imprisonment, nor does it seek to give a comprehensive picture of Tibetans released from prison and their sufferings.

A full and detailed accounting is not always possible given the tight controls on information flow by Chinese authorities and the dangers faced by Tibetans in passing along information to the outside world. Moreover, China does not allow independent nongovernmental organizations to freely conduct research or monitor human rights issues inside their borders. As a result, obtaining and verifying credible information presents great challenges.

This report documents the deaths of 14 Tibetans following varying periods of imprisonment, and details where possible information about their treatment in custody.

The cases listed in the report come from information gathered by ICT from sources inside and outside Tibet, and information published by Chinese state media and Tibetan exile media outlets and organizations.

3. THE NEED FOR SUPPORT – RELEASED TIBETAN POLITICAL PRISONERS

“One of his legs was cut with many bloody knife wounds and a nail had been driven in to a toenail on his right foot. A great deal of flesh had been cut away from his bottom, where the wound was rotting and infested with insects. Where his waist had been beaten with electric batons, the flesh had started to decay. There were many wounds on his back and on his face. One of the wounds was covered with transparent tape. Because he had not received any medical care, he was already on the verge of death.”

A Tibetan blogger writing in Chinese about twenty-eight year old Tibetan Tendar who died following severe torture.

Tibetan writer Tashi Rabten was met by hundreds of Tibetans bearing khatags in his home area upon his release from four years in prison in March, 2014.

While many more remain in prison for peaceful expression of their views, those Tibetans who are released cannot be said to experience freedom. Perceived by the authorities as a threat to the state, former Tibetan political prisoners face isolation, fear and anxiety, in addition to chronic health conditions, pain and trauma.[6] Some do not survive, like 43-year old Goshul Lobsang, who never recovered from injuries due to torture and malnourishment in prison and died at home in March, 2014, soon after his release.

Former political prisoners are perceived by the authorities as a threat to the Party-state because of the views and actions that led to their sentencing. Additionally, many former political prisoners are oftentimes publicly welcomed and greeted upon their release and return to their respective communities. For example, Tashi Rabten, editor of banned literary magazine “Eastern Snow Mountain” (Tibetan: “Shar Dungri”), was sentenced on June 2, 2011, by the Ngaba (Chinese: Aba) Intermediate People’s Court in Sichuan (the Tibetan area of Amdo). In an impressive display of solidarity, Tashi Rabten was met by hundreds of Tibetans bearing khatags in his home area upon his release from four years in prison in March 2014. As many other former political prisoners, Tashi Rabten has apparently become a rallying point for Tibetan solidarity and dissent.

The intention of the authorities is to control and isolate these former prisoners, and to create a visible deterrent to other Tibetans who may seek to express views that are counter to those of the Beijing leadership.

Many of the prisoners detailed in this report were detained after 2008. By keeping most of them in jail for the full length of their sentences, the Chinese state underlines its intent to crackdown on dissent.

- This report provides accounts of the imprisonment and release of a prominent Buddhist lama, Buddhist nuns and monks involved in peaceful demonstrations in 2008, long-serving political prisoners and young laypeople.

- The length of imprisonment for Tibetans whose cases are documented in this report varies widely – two of those in this report were sentenced to over two decades in prison, while another spent eight months in detention, without charge. The 29 Tibetans whose cases are documented in this report were imprisoned for participating in political protests, writing essays and literature, or possession of images and DVDs of the Dalai Lama and charged with violating national security laws. Most were forced to serve the full length of their sentence, though, for reasons that remain largely unclear, some of them were released prior to the end of their sentences. This may be due to specific local circumstances, rather than being indicative of a pattern of lenient release. In at least one case, the authorities may have feared the prisoner would die following torture, which has commonly been a reason for early release.

- The level of violence directed at Tibetan political prisoners is frequently extreme and results in Tibetans being left with severe scars following a period of detention, including paralysis, the loss of limbs, organ damage, and serious psychological trauma.

- Typically, former prisoners face profound fear and anxiety upon their release, combined with a constant awareness of being under surveillance. Their psychological suffering is often heightened by the knowledge that their family and friends are also under pressure from the authorities. They often suffer from severe financial hardship as they are dependent on their families, often unable to find work due to their status as a former political prisoner. Monks and nuns are not permitted to return to their monasteries or nunneries. Sometimes they cannot afford medical treatment needed following severe torture or years of poor nutrition in prison.

- Often Tibetans whose lives might have been saved following torture die because of deliberate withholding of medical treatment, as in several cases documented in this report. This contravenes both international and Chinese Criminal Law regarding medical access for detainees.[7] In August 2014, four Tibetans died of a combination of untreated wounds and torture in custody after paramilitary troops opened fire into a group of Tibetan demonstrators in Sershul, Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi), Sichuan.[8] This also occurred in earlier incidents where Tibetans were initially injured by either gunfire or beatings while being taken into custody.[9] Although the initial injuries may not have been life-threatening, torture following detention has in a number of cases led to dramatic deterioration and death. Similarly, in March, 2008, Tibetans taken into custody with bullet wounds were rarely given medical treatment according to sources.[10] According to anecdotal reports from Lhasa, the worst torture was carried out by People’s Liberation Army and People’s Armed Police troops brought in from outside the city.[11]

- There are no indications of investigations into allegations of torture and mistreatment, let alone into cases of Tibetans who have been subjected to arbitrary detentions.[12] Financial aid or compensation for injuries suffered during detention are extremely rare.[13] This is despite Chinese official assertions that China’s legislative administrative and judicial departments have adopted “forceful measures against torture”. Dr. Xia Yong, deputy director of Law Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, was cited in Chinese official media in March, 2001, as saying: “Relevant regulations adopted by the State Council in 1996 and 1997 have played a significant role in preventing policemen from torturing criminal suspects and punishing them for such acts.”[14]

- Prison sentences are usually followed by a period of “deprivation of political rights”, which deprive the individual of, among other things, “the right to freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession, and of demonstration”.[15] While these are rigorous in themselves, the scope of “deprivation of political rights” does not cover all of the restrictions that Tibetan former prisoners experience.

4. ‘HE WAS A SHELL OF HIS FORMER SELF’: TORTURE OF TIBETAN PRISONERS

“I cry not only for my son who died a tragic death, I cry even more for those sons who sons who are being tortured. As a mother, I can’t imagine the torments and suffering my son endured in prison.”

The mother of Tendar, a Tibetan man in his late twenties, who died as a result of torture after being detained trying to help an elderly monk.[16]

Brutal torture has been consistently reported by Tibetan political prisoners since the earliest days of Communist Party rule in Tibet. Palden Gyatso, a Tibetan monk who was arrested in 1959 and spent 33 years in prison, was first tortured in 1960 when his arms were wrenched out of their sockets by a team of Chinese interrogators.[17] He later lost all of his teeth after an electric cattle prod was activated inside his mouth.

But since 2008, there is evidence that torture has become more widespread and directed at a broader sector of society in the context of a deepening crackdown in Tibet. A number of detailed accounts, documenting extreme brutality while in detention, have emerged in the past five years.

Labrang Jigme, a Tibetan monk who was detained first in 2008, gave a rare video testimony, uploaded onto Youtube, of torture following the March, 2008 protests. Speaking on camera later, he gave an account that was chilling in its detail of his treatment, and consistent with other accounts received by ICT.[18]

“I was put on a chair with my hands tied at the back. A young soldier pointed an automatic rifle at me and said in Chinese, “This is made to kill you, Ahlos [derogatory term used for Tibetans by some Chinese]. You make one move, and I will definitely shoot and kill you with this gun. I will throw your corpse in the trash and nobody will ever know.”

Later he was subjected to days of abuse: “They would hang me up for several hours with my hands tied to a rope… hanging from the ceiling and my feet above the ground. Then they would beat me on my face, chest, and back, with the full force of their fists. Finally, on one occasion, I had lost consciousness and was taken to a hospital. After I regained consciousness at the hospital, I was once again taken back to prison where they continued the practice of hanging me from the ceiling and beating me. As a result, I again lost conscious and then taken to the hospital a second time. Once I was beaten continuously for two days with nothing to eat nor a drop of water to drink. I suffered from pains on my abdomen and chest. The second time, I was unconscious for six days at the hospital, unable to open my eyes or speak a word.

“In the end, when I was on the verge of dying, they handed me over to my family. At my release, my captors lied to the provincial authorities by telling them that that they had not beaten me. Also, they lied to my family members by telling them that they had not beaten me; they also made me put down my thumbprint (as a signature) on a document that said that I was not tortured.”

Other known cases from 2008 involved two Tibetan men named Tendar and Paltsal Kyab.[19] Tendar was shot by the police while attempting to intervene on behalf of an elderly monk they were beating, and was subsequently taken away and beaten repeatedly by teams of Chinese police, who used iron rods on him and burned his skin with cigarette butts. He later passed away. In the case of Paltsal Kyab, although officials said that he had died “of natural causes” while being held in custody, when the body was released to the family there were clear signs of torture and brutal beatings. His younger brother, who now lives in exile, told ICT that according to witnesses who saw his body, “The whole front of his body was completely bruised blue and covered with blisters from burns. His whole back was also covered in bruises, and there was not even a tiny spot of natural skin tone on his back and front torso. His arms were also severely bruised with clumps of hardened blood.”

A further report of torture comes from Golog Jigme, the Tibetan monk who helped Dhondup Wangchen film the documentary Leaving Fear Behind. He found himself pursued and harassed by the police in retaliation, and was eventually taken into police custody. Speaking with ICT after his daring escape from Tibet,[20] Golog Jigme said that “[the authorities] had tried to torture me to death… The treatment we received in prison was underpinned by a determination to defeat our spirits. In prison, they were literally trying to kill me. They want to kill prisoners like me.”

Tibetan writer Kunsang Dolma gives an account of a detention of a relative under suspicion of involvement in protests in 2008 that is typical of many ‘disappearances’ and incidents of torture. “[My cousin’s son] was never formally charged with any crimes, did not receive a trial, and no explanation was given to his family about what was happening or when he would get out. The family didn’t know whether he was dead or alive. His family even thought it might be good if he were dead because death is better than torture. […]

“My cousin’s son was released six months after he disappeared. He came out a shell of the person he used to be. While in jail, he had been kept in a dark room where the police repeatedly questioned him about the identities of other people at the protest, to which he only answered that he wasn’t there and didn’t know who was. He […] was nearly dead from the brutality when he got out. When he left the jail, he saw sunlight for the first time since his capture, and he was amazed at the sight of the green grass outside. He was only seventeen years old.”[21]

Some former prisoners report procedures such as medical injections that cause immense pain. Goshul Lobsang, who died in March 2014 following his release from custody, apparently received injections that caused immense pain. It is not known what these injections could have been but they may have been administered by medical personnel.[22] Police also used sharp-pointed objects such as toothpicks to repeatedly pierce and penetrate into the tops of Goshul Lobsang’s finger nails and cuticles. This stabbing, applied with force and consistency, resulted in severe bleeding, swelling and pain making Goshul Lobsang unable to temporarily use his hands, according to a report by the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy.[23]

“I might lose this bony and haggard body…” – Tibetans who did not survive imprisonment

“I am an ordinary nomad who loves his people, so I am willing to do anything for my people. I might lose this bony and haggard body that has suffered brutal pain and torture inflicted out of sheer hatred, I still will not have any regrets. I have the desire to follow in the footsteps of martyrs who expressed everything through flaming fire, but I lack courage [to do such a thing].”

From the last note of Goshul Lobsang, who died following torture in March 2014[24]

Since protests broke out across Tibet in March 2008, the Chinese government has sought to block information from reaching the outside world on the torture, disappearances and killings that have taken place across Tibet. Hereafter, this report details the deaths of 14 Tibetans in different areas of Tibet as a result of being subjected to excessive brutality in custody. They are not isolated incidents; other deaths following torture have occurred, but full details are often not known.

GOSHUL LOBSANG

“He could not say anything, but simply folded his hands and died.”

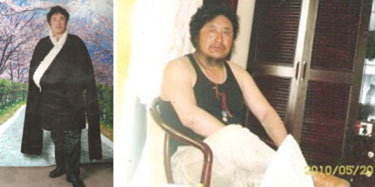

Goshul Lobsang, 43, died at home on March 19, 2014, following severe torture during his imprisonment. Goshul Lobsang, who was accused of being an organizer of a protest in 2008, had been beaten so severely that he could not even swallow his food. Images of him at his family home in the days before his death showed him looking emaciated and close to death at his family home in Machu (in Chinese, Maqu) county in the Kanlho (Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Amdo, today a part of northwestern China’s Gansu province.

Goshul Lobsang, 43, died at home on March 19, 2014, following severe torture during his imprisonment. Goshul Lobsang, who was accused of being an organizer of a protest in 2008, had been beaten so severely that he could not even swallow his food. Images of him at his family home in the days before his death showed him looking emaciated and close to death at his family home in Machu (in Chinese, Maqu) county in the Kanlho (Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Amdo, today a part of northwestern China’s Gansu province.

Goshul Lobsang was so ill that in the weeks before his death he could barely speak, but according to Tibetan sources, he still managed to utter some sentences about the well-being of the Tibetan people and the importance of freedom in Tibet. According to the same sources, among his final words were that he did not regret his death, because he had done what he could, and what he felt compelled to do.

Goshul Lobsang was born in a small village in Machu, and spent some years in India studying at an exile Tibetan school before going back to Tibet to continue his nomadic life.[25]

According to Tibetans who knew him, in the 1990s, following his return from India, a number of leaflets with a political content were disseminated in Goshul Lobsang’s home area. Goshul Lobsang was detained under suspicion of involvement but was released a few weeks later. However, he remained under suspicion. As this report shows, Tibetans who are detained even for a short period by the Chinese authorities remain under close surveillance and they are subject to even more attention if they have travelled to India, as they are perceived to have come under the influence of the ‘Dalai clique’.

Due to the restrictions he experienced, Goshul Lobsang finally left Machu and travelled to Lhasa, where he lived for a couple of years. He returned to his home town after 2000, and began to teach short English language courses to nomad students in order to further their opportunities for obtaining work. He was known among his friends to be a strong and determined individual who had on occasion raised a handmade Tibetan flag above his nomadic tent.[26]

In March, 2008, as unrest rippled across the Tibetan plateau, major protests were held in Machu county, including in Goshul Lobsang’s hometown area, on March 17-19. According to Tibetan sources, Goshul Lobsang was involved in the protests.

In 2009, leaflets circulated in the area encouraging people not to celebrate Tibetan New Year; this was a development that occurred across Tibet. It was a heartfelt demonstration of solidarity with protestors who were suffering in prison or who had died, and an expression of mourning and grief. In Machu, the leaflets also encouraged local people to monitor the situation and to inform others about the reality of the oppression.

On April 10, 2009, an incident occurred which led to Goshul Lobsang’s detention. Although details are sketchy of the circumstances, it appears that Goshul Lobsang and some other Tibetans challenged some of the armed forces about their presence and methods. When Goshul Lobsang and another Tibetan named as Dakpa were detained, local people managed to argue with the armed forces and to secure their release. Although the paramilitary forces then backed down slightly from the township, officials demanded the detention of ‘leading separatists’ including Goshul Lobsang, and demanded that they were handed in by local people.

Goshul Lobsang and several others remained in hiding in the mountains for some time, until 2010, when he decided to return to normal life. He told one of his friends that if he were to be caught again, then he would bear the consequences.

He was detained in June, 2010, and spent five months in the main detention center in Machu. According to a Tibetan source familiar with the case, he was subjected to intensive interrogation, brutality, and deprivation of both sleep and food. On November 26, 2010, Goshul Lobsang was sentenced to ten years in prison and transferred to Dingxi city in Gansu province. At his trial, he was said to be in such a critical condition that he had to be supported by two police officers.

In November 2013, Goshul Lobsang’s health took a turn for the worst and the authorities decided to release him so that he would not die in custody. Despite making every effort to provide him with medical treatment, Goshul Lobsang was not even able to swallow food and did not recover.

As he was dying, he told friends that while he knew it was ‘selfish’ to request it, his wish as a humble Tibetan nomad was for the Dalai Lama to bless him, and secondly he wanted to let the outside world know about the life of Tibetan political prisoners under Chinese oppression.

He passed away in his bed at home surrounded by family members; Tibetan sources said that: “[At the end] he could not say anything, but simply folded his hands and died.” He leaves his mother, wife, and a teenage son and daughter.

NORLA and BULUG

Former political prisoner Norlha (known by only one name) passed away in Lhasa on December 27, 2011, following torture in prison, according to Tibetan exile sources.[27]

Former political prisoner Norlha (known by only one name) passed away in Lhasa on December 27, 2011, following torture in prison, according to Tibetan exile sources.[27]

Bulug, a Tibetan in his mid fifties, who was sentenced at the same time as Norlha, passed away in hospital on March 25, 2011.[28]

Norlha, who was in his late forties, was born to the Ashak Tsang family in Pema Township, Jomda (Chinese: Jiangda), Chamdo (Chinese: Qamdo) in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Bulug was born in Dzorgang Township also in Jomda.

In 2008, Tibetans in Norlha and Bulug’s home area of Jomda had developed a new means of demonstrating their solidarity. Some farmers had stopped farming as a form of resistance. In June 2009, the Chinese authorities enforced an intense patriotic education campaign in Kyaptse monastery and sought to compel monks to denounce the Dalai Lama as a ‘separatist’. Monks remained silent, refusing to denounce His Holiness, and later many ran away from the monastery. Except for the presence of the patriotic education work team, the monastery was empty. Police and officials arrived in the area and sought to compel the monks to return.

The authorities threatened local officials to force monks to return, and then detained several Tibetan officials as a warning. Both Norlha and Bulug were leading figures from the local community who sought their release. According to the same Tibetan sources, they were then detained in the ensuing crackdown.

In August, 2009, Norlha and Gonpo Dargye, blamed for being the lead organisers of the protest, were sentenced to two years in prison. According to Tibetan sources, Norlha was brutally tortured and his health almost destroyed. He was also denied medical treatment.

Norlha was released in 2011, but his health condition continued to deteriorate. Despite being taken to a leading hospital in Chengdu on several occasions, he passed away on December 26, 2011.[29]

Bulug was also subjected to severe torture in custody over many months, and he was also denied medical treatment. Family visitors were also restricted. He died in hospital on March 24, 2011.

YANGKYI DOLMA

According to various Tibetan sources, Yangkyi Dolma had staged a demonstration along with another nun from Lamdrag nunnery named Sonam Yangchen, shouting slogans calling for the return of the Dalai Lama, human rights for Tibetans, and religious freedom. Both nuns were severely beaten by the security forces at the site of the demonstration at the Kardze County main market square on March 24, 2009. She died on December 6, 2009, in Chengdu hospital. It is not known whether Yangkyi Dolma had been sentenced.

Following the incident, at around 7 pm in the evening, paramilitary police raided Yangkyi’s family home, ransacked the portrait of the Dalai Lama and rebuked the family members for being the supporter of ‘separatist forces’.[30]

THUPTEN LEKTSOG

A Tibetan monk called Thupten Lektsog from Draklha Ludrig monastery[31] in Lhasa never recovered from severe torture in custody after a period of imprisonment following his participation in peaceful protests in October, 1989. He died in January, 2010, according to Tibetan exile sources.

Thupten Lektsog was born in Meldrogungkar (Chinese: Mozhu Gongka), Lhasa municipality, the Tibet Autonomous Region. Together with other monks from his monastery, he participated in the demonstrations in Lhasa in 1989, displaying the Tibetan national flag. During the following crackdown and imposition of martial law in Tibet’s capital, Thubten Lektsog was arrested and they were subjected to brutal torture in Gutsa detention center in Lhasa. He was later sentenced to three years in prison, where he continued to be tortured. Thubten Lektsog’s hands and legs were broken, he was beaten so badly that he vomited blood and lost consciousness, and he eventually became paralysed. He died at his home in January, 2010.

NGAWANG YONTEN

Ngawang Yonten, a Drepung monk from Lhundrub (Chinese: Linzhou) county in Lhasa municipality, was arrested after he participated in protests in Lhasa in March, 2008.[32] Tibetan sources told ICT: “Before his detention, Ngawang Yonten was one of the healthiest, strongest monks in his group.” He suffered from severe torture in prison and died while still in custody. The authorities did not, at first, return his body to his family. Following appeals to senior officials, his body was finally returned for traditional funeral rites.[33]

PEMA TSEPAK

Pema Tsepak, 24, a resident of Punda town in the Dzogang county of Chamdo prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region, died after torture following his detention for participating in a peaceful protest in January, 2009. Tibetan sources told Radio Free Asia that the Chinese authorities were trying to cover up the circumstances of Pema Tsepak’s death, saying that he jumped off a building. A local Tibetan said: “We believe he was beaten to death and then thrown off the building.”[34]

A Tibetan living in Delhi, India, said in an interview with RFA that Pema Tsepak had been hospitalized following mistreatment at the hands of his captors. “He was so severely beaten that his kidneys and intestines were badly damaged. He was initially taken to Dzogang [county] hospital, but they could not treat him, and they took him to Chamdo hospital instead,” the Tibetan source said.[35]

A convoy of 18 vehicles, including army trucks carrying soldiers and officials, arrived in Punda town and began searching the homes of other detainees following the protest. They took away pictures of the Dalai Lama, and informed Pema Tsepak’s family that he had committed suicide.

Pema Tsepak, Thinley Ngodrub, 24; and his brother Thargyal, 23, had been detained on January 20, 2009, as they walked towards the local police headquarters in Tsawa Dzogang. They were carrying a white banner reading “Independence for Tibet,” distributing fliers, and shouting slogans against Chinese rule, according to Tibetan sources.

THINLAY

Thinlay, who was from a village in Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan Province, participated in a peaceful protest in the area in April, 2009, according to exile Tibetan sources. Together with several other Tibetans, he was detained without trial for seven months. According to the same sources, he was broken by the torture; nearly half his body was paralysed, and he suffered from extreme psychological trauma. After seven months, he was released to his family. Despite medical attention, Thinlay died on August 10, 2011. Doctors reported that he had suffered from irreversible brain damage.

NGAWANG JAMPEL (Ngawang Jamyang)

A senior Tibetan Buddhist scholar monk Ngawang Jampel (also known as Ngawang Jamyang) died in custody in December, 2013. Ngawang Jampel, 45, was among three monks from Tarmoe monastery in Driru (Chinese: Biru), who ‘disappeared’ into detention on November 23, 2013 while on a visit to Lhasa. This followed a police raid on the monastery, which was then shut down, and paramilitary troops stationed there.[36]

Less than a month later, Ngawang Jampel, who had been healthy and robust, was dead, and Tibetan sources in contact with Tibetans in Driru said it was clear he had been beaten to death in custody. Ngawang Jampel had been one of the highest-ranking scholars at his monastery and had founded a Buddhist dialectics class for local people. He gave free teachings on Tibetan Buddhism and culture to lay people and monks, and was known for his skills in mediation in community disputes.

According to the same Tibetan sources, Ngawang Jamyang was born in 1968 in Nakshul Township, Driru in Nagchu (Chinese: Naqu) in the Tibet Autonomous Region. He joined his local monastery in 1987. Two years later, he escaped to India where he joined Sera monastery in exile in south India. He became known for his intense focus on study and dedication to Tibetan Buddhism, and was admired by many young monk students in Sera. In 2007, he decided to return to Tibet because he felt so strongly about the need for educated monks to help preserve the culture and religion inside Tibet.

YESHI TENZIN

Yeshi Tenzin, who was accused of disseminating political leaflets, died after being released from a ten-year prison sentence in December, 2010.[37]

Yeshi Tenzin had attended a major religious ceremony led by the Dalai Lama in exile in India in early 2000, and upon his return he was accused of organizing the dissemination of leaflets deemed as ‘separatist’. He served his prison sentence in Tibet Autonomous Region Prison, known as Drapchi, and later in Chushur (Chinese: Qushui) prison, also in Lhasa.

Yeshi Tenzin died ten months following his release, on October 7, 2011, in hospital in Lhasa. Tibetan sources said that half of his body was paralyzed, and that he had been deprived of medical treatment despite enduring severe torture.

TSERING GYALTSEN

On January 23, 2012, security forces in Luhuo (Draggo) County, Ganzi (Kardze) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan fired at a crowd of protesters, wounding at least 32 and killing at least one – Norpa Yonten, a 49-year-old layperson.[38] According to some reports, the protesters were demonstrating against the arbitrary detention of Tibetans and calling for the return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet and for additional self-immolations if Tibetans’ concerns were ignored. According to a report published by the exile Tibetan website Phayul.com, Tsering Gyaltsen, a monk from Draggo Monastery in Luhuo County, died February 9 from injuries sustained after being beaten by police who were arresting him for allegedly participating in the January 23 protest.

A Tibetan source said: “Relatives went to local officials to try to find out where he was, but they had no success. Later it was learnt that he had been tortured mercilessly and we heard his spine was broken among other injuries.” The same sources also learnt that Tsering Gyaltsen had been taken from detention to the main military hospital in Kardze prefecture for medical treatment, but that this was too late to save his life. He died in May, 2012, in hospital and his body was never returned to the family.

TENDAR

Twenty-eight year old Tendar’s death following torture after his arrest for trying to help an elderly monk was featured in a video released by the Central Tibetan Administration in March 2009.[39]

A Tibetan blogger writing in Chinese described the images as follows: “One of his legs was cut with many bloody knife wounds and a nail had been driven in to a toenail on his right foot. A great deal of flesh had been cut away from his bottom, where the wound was rotting and infested with insects. Where his waist had been beaten with electric batons, the flesh had started to decay. There were many wounds on his back and on his face. One of the wounds was covered with transparent tape. Because he had not received any medical care, he was already on the verge of death.”

Tendar worked in the customer services department of a Chinese telecommunications company and lived in Lhasa. On March 14, 2008, when Tibetan protests turned violent on the streets of Lhasa, Tendar witnessed an elderly monk being beaten by Chinese security personnel. Although details of what happened are sketchy, according to reports by Tibetans who know Tendar, and others in Lhasa on that day, it seems that Tendar tried to help the monk, by telling the police to have mercy on him. He did so at a time when armed police were opening fire on the rioters. Tendar was shot and fell to the ground. Still conscious, he was taken away by police.

A Tibetan source who was in Lhasa after the incident and spoke to Tibetans who know Tendar said: “The injury didn’t appear to be life-threatening. I was told that he was taken to the Lhasa General Hospital that is run by the People’s Liberation Army. While he was at the hospital, a team of four to five Chinese security personnel visited him every four to six hours. During those times they took turns in beating him while interrogating him about his involvement [in the March 14 protests]. They were using iron rods and cigarette butts to burn his skin. He was tortured repeatedly and his condition deteriorated rapidly.”

At this time, none of Tendar’s family or friends knew where he was, a pattern consistent with the wave of disappearances that took place after March 14, and that is still occurring in some areas. Through connections, Tendar’s family managed to locate him. When they were allowed to visit, he was “in shock, and in excruciating pain. Every movement of his body would cause him to scream with pain”, said the same Tibetan source. He was unable to walk and his body appeared to be paralysed from the waist down. Tendar said that he had witnessed a Tibetan monk at the hospital being beaten to death with iron bars by security personnel. He begged to be taken home.

The same Tibetan source said: “While at hospital, Tendar had tried to kill himself twice by jumping off the window from his room. He had managed to drag his body to the window but was unable to get out as he could not move the lower part of his body.”

The Tibetan source believes that Tendar was only released to his family as the authorities knew there was no hope of his recovery. This is consistent with other cases where Tibetans have died after torture; the authorities seek to avoid being responsible for a person’s death while they are under their charge. His relatives attempted to get medical care for him but hospitals were reluctant to take him into their care due to the political sensitivity of a patient who had been involved on March 14. Tendar was finally admitted to the Peoples’ Hospital near the Potala Palace, where he was immediately taken into intensive care. The Tibetan source said: “Some of the nursing staff had tears in their eyes when they saw the serious nature of his injuries.”

Tendar spent 20 days in hospital and his condition continued to deteriorate. He became unconscious, and medical staff told his family that there was nothing more they could do for him. Tendar’s family had to pay a medical bill of 90,000 yuan ($13,000) before they could take him home.

Tendar died at home 13 days later, on June 19, 2008. Video footage obtained by the Tibetan government in exile depicts vultures at his sky burial site at Toelung, west of Lhasa. The same Tibetan source, who is no longer in Tibet but who spoke to eyewitnesses, said: “One could see on his body the marks of iron rods. His body was nothing but bone and skin. When his body was being prepared for the vultures [a ritual called Jhador in Tibetan], a slender metal bar or long nail about one-third of a meter in length was found inserted through the bottom of his leg. This appeared to be one of the torture instruments used during interrogation.”

The story of Tendar’s death became well-known in Lhasa and has even been written about by Tibetan bloggers in Chinese. Many people who did not know Tendar but who had heard about him came to mark his death at important dates afterwards. “Those who were fearful of attending these occasions due to being seen by security personnel sent money and khatags [white Tibetan blessing scarves],” said the same source.

A Tibetan writer said: “Several hundred Tibetans came to his funeral services. Many came out of deep sympathy for a stranger who suffered a terrible tragedy. At the funeral service, Tendar’s mother said sadly, ‘I cry not only for my son who died a tragic death, I cry even more for those sons who sons who are being tortured. As a mother, I can’t imagine the torments and suffering my son endured in prison.’”

PALTSAL KYAB

On May 26, 2008, two local township leaders in Charo township, Ngaba (Chinese: Aba), Sichuan (the Tibetan area of Amdo) came to tell the family of 45-year old nomad Paltsal Kyab, also known as Jakpalo, that he was dead. Although officials said that he had died “of natural causes” while being held in custody following a protest in the area on March 17, 2008, when the body was released to the family there were clear signs of torture and brutal beatings.

Paltsal Kyab’s younger brother, Kalsang, who now lives in exile, told ICT that according to witnesses who saw his body, “The whole front of his body was completely bruised blue and covered with blisters from burns. His whole back was also covered in bruises, and there was not even a tiny spot of natural skin tone on his back and front torso. His arms were also severely bruised with clumps of hardened blood.”

Paltsal Kyab, who was married with five children, was taken into custody following a peaceful demonstration that occurred in Charo on March 17, 2008. According to anecdotal accounts from the area given to Paltsal Kyab’s brother, around 100 young Tibetans held a protest on the main street “because they believed that the United Nations and foreign media chose not to listen to and see the truth in Tibet.” The Tibetans began to talk about burning a building down. According to his brother, Paltsal Kyab told the Tibetans that it was important not to take this action, saying: “We Tibetans must follow His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s non-violent path. Our only weapon is our truth. The building belongs to the government, but several Tibetan and Chinese families are living in there.” At least three people in a building nearby testified to police that Paltsal Kyab had persuaded the Tibetans not to be violent, according to Kalsang.

After the incident, according to his friends, Paltsal talked about going to the police station to tell officers that he had not committed any violation such as destroying buildings or cars, or harming anyone. But he heard from his friends that his name was already on the wanted list, and that individuals who were detained were being badly beaten. Paltsal went to see a relative who was ill out of town.

On April 9, 2008, at around midnight, 11 police raided Paltsal’s home, while a truckload of armed soldiers waited outside. According to reports from the family, one police officer pointed a gun at the head of Paltsal’s 14 year old son and asked him where his father was. His son replied that his father had gone to see his relative who was ill. Paltsal’s wife was then dragged out of her room and asked the same question. She gave the same answer as her son, but gave a different name of the relative. Because they had given different names, the police claimed that they were lying, and Paltsal’s son was taken into custody. On arrival at the police station the teenager was slapped, kicked and punched for hours during interrogation. He was released the next day.

When Paltsal was told about his son, he came home immediately. Kalsang said: “Our family had heard that the Chinese government says that people involved in protest must surrender voluntarily and that people who did so would be treated leniently, as opposed to people who are seized by police. Paltsal’s relatives told him that he was a father of five children so that it wouldn’t be possible for him to hide from police throughout his life. Paltsal also knew that his son had been beaten and interrogated. So he decided to surrender voluntarily.”

On April 17 or 18, 2008, Paltsal went to the local police station and gave himself up. He was held there for two weeks and then transferred to a detention center in Ngaba on April 27, 2008. The family heard nothing about his condition or whereabouts until May 26, 2008, when two local township leaders came to Paltsal’s home to inform his wife and children of his death.

Paltsal’s family members were allowed to collect his body from the detention center. Kalsang says: “Upon arrival, the relatives were told by the Ngaba police that the cause of his death was sickness, not torture. They also allegedly claimed that they had taken him to a hospital twice because of his kidney and stomach problems. But his relatives said that when Paltsal went to the police station to surrender he was a normal healthy man with no history of any major health problems. The police officers never acknowledged the cause of death as torture but they immediately started to offer money to the family. The family was not allowed to take photos of his body or tell anyone anything about what had happened.”

Kalsang said that he was later informed by various sources that his elder brother had been very badly tortured in custody. Family members asked for permission to take his body to Kirti monastery in Ngaba. It is important in Tibetan culture for prayers to be said for a person immediately after his death in order to help ensure a peaceful transition. But the army refused permission. Kalsang said: “They even could not take Paltsal’s body to Kirti monastery to pray for Paltsal’s soul.”

Paltsal was given a traditional sky burial, with police officers present, including two senior Tibetan police officers. Kalsang said: “It was obvious from the condition of Paltsal’s body that he had suffered an agonizing and painful death due to severe torture, not of natural causes.” Those preparing his body for burial, which involves dismemberment, told the family that there was severe damage to his internal organs, including his small intestines, gall-bladder and kidneys.

DEATH OF A TIBETAN NGO WORKER FROM LHASA FOLLOWING TORTURE

Tenzin Choedak, a 33-year old young NGO worker, died on March 19, 2014, less than six years into his 15-year jail term and following severe torture in prison.

Tenzin Choedak, also known as Tenchoe, aged 33, did not recover from injuries sustained while in police custody following his arrest for involvement in protests against Chinese rule in Lhasa in March, 2008, according to the India-based NGO Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy.

Quoting a local eyewitness cited by TCHRD, Tenchoe was taken to hospital just before his death with his hands and legs heavily shackled. “He was almost unrecognizable,” said the source. “His physical condition had deteriorated and he had a brain injury in addition to vomiting blood.” The authorities sought to treat him in three hospitals, but when his condition continued to worsen, released him to the care of his family. He died two days later at the Mentsikhang, the tradition Tibetan medical institute in Lhasa, just hours after his family took him there.

Tenzin Choedak, who was born in Lhasa, escaped into exile as a child and was educated at Tibetan Children’s Village school in India for a few years. In 2005 he returned to Lhasa, and joined a European NGO affiliated to the Red Cross.

Tenchoe was arrested in April, 2008, accusing him of being one of the ringleaders of the March protests, and he was sentenced to 15 years in prison, according to the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy. He was imprisoned in Chushur (Chinese: Qushui) Prison on the road to Shigatse outside Lhasa.

RELEASED PRISONERS: THE URGENT NEED FOR JUSTICE

TORTURE FOLLOWING PEACEFUL POLITICAL PROTEST: DHONDUP

Thirty-year old Dhondup[40] was released from prison on May 20, 2013 after he served a one year and two month term on charges of “splittism” for his participation in a large-scale peaceful protest against the Chinese government. Dhondup was severely tortured over the course of several weeks while in detention prior to his sentencing, sustaining damage to his wrists from being handcuffed and hung in the air. It is a common for authorities to handcuff and hang Tibetan political prisoners for hours at a time, or even for an entire night, during interrogation.

The charges against him stem from a protest held on January 15, 2012, at which Dhondup, along with local Tibetans and monks from Bha Shingtri monastery, held a peaceful demonstration against the Chinese government. Dhondup and several other protestors were subsequently arrested and later sentenced by the Gepa Sumdo (Chinese: Tongde) county Intermediate People’s Court on March 19, 2013 on charges of “splittism.” While it is unknown if Dhondup was one of the organizers of the protest, it is common for authorities to target those who they view as ringleaders for arrest and abuse. The charges and prison terms for those arrested with Dhondup remain unclear.

Dhondup served his sentence at a local prison in Gepa Sumdo county, the same location where he was tortured during interrogation before his trial.

Dhondup was born in the village of Palchok Ponkor, located in Gon Kongma township, Township, Gepa Sumdo, Tsolho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (Chinese: Hainan) in Qinghai province.

TIBETAN INTELLECTUAL ‘UNRECOGNIZABLE’ AFTER PRISON TERM

Jigme Gyatso, a 28-year Tibetan intellectual and former monk, was released from prison on April 17, 2013, in very poor health. His condition remains weak and his eyesight badly damaged due to the torture and hard labor he was subjected to in prison. He also suffers from kidney damage and back problems as a result of his imprisonment.

Jigme Gyatso, a 28-year Tibetan intellectual and former monk, was released from prison on April 17, 2013, in very poor health. His condition remains weak and his eyesight badly damaged due to the torture and hard labor he was subjected to in prison. He also suffers from kidney damage and back problems as a result of his imprisonment.

A Tibetan who visited Jigme Gyatso in person after he was released said, “We grew up together in the same hometown and monastery, and yesterday I could not recognize Jigme Gyatso, due to his deteriorated health condition, and during our conversation, I could tell his mental health is not as good as it was before.”

Jigme Gyatso was arrested in October 2011, by the Public Security Bureau in Tsoe City, Kanlho (Chinese: Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Gansu province. He was sentenced to three years imprisonment on January 14, 2012 by the Intermediate People’s Court in Tsoe City. He was accused of visiting Tibetan areas, including Rebkong, and encouraging students to protest against government policies regarding the use of Tibetan language in the region. In addition, the Kanlho Public Security Bureau detained two of Jigme Gyatso’s close friends and took them to the provincial capital of Lanzhou for interrogation, before releasing them two weeks later.

Jigme Gyatso was born in Keysen township, Yugan (Chinese: Henan) Mongolian Autonomous County, Malho (Chinese: Huangnan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai province. He joined Labrang monastery in 1995 and began studying Tibetan Buddhism, later joining the Labrang Buddhist Institute of Gansu province in August 2006, graduating in 2010 with a concentration in Tibetan education. He has published articles in numerous newspapers and magazines on various topics, however since 2008, Jigme Gyatso, as well as many other Tibetan writers, turned his attention to strongly expressing support for the freedom and human rights of the Tibetan people, and wrote critically of Chinese policies in the region.

Jigme Gyatso, nicknamed ‘America,’ disrobed and left the clergy in 2010 and joined a local song and dance group called ‘Kelsang Metak Song and Dance Troupe’, and travelled to a number of places across Tibet for performance before his arrest. He also wrote about several Tibetan political prisoners via social media and articles.

TORTURE LEAVES MONK WITHOUT USE OF HIS HAND AFTER AUTHORITIES FOUND PHOTOS OF DALAI LAMA

Namgyal Tseltrim, a Tibetan Buddhist monk, was released from prison in Lhasa on May 11, 2013, after spending nearly eight months in detention without formal arrest, charges, or sentencing. During his detention, he suffered severe torture, which left him without the use of his right hand.[41]

Namgyal Tseltrim, a monk at the historic Tsenden monastery in Nagchu prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region, was initially detained from the monastery on October 6, 2012, by the local Public Security Bureau (PSB). According to a Tibetan source from the region, authorities found photos of the Dalai Lama, along with DVDs of Buddhist teachings by the Dalai Lama, in Namgyal Tseltrim’s residence at the monastery. Authorities subsequently accused Namgyal Tseltrim of “separatism”. After approximately five months of torture and interrogation at the local PSB station and Nagchu, Namgyal Tseltrim was transferred to Toelung detention facility in Lhasa municipality, where he was further interrogated and held without charge for nearly three months.

Namgyal Tseltrim was born in the Kham region of Tibet, in Yala township, Sog (Chinese: Suo) county, Nagchu (Chinese: Naqu) prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region. His monastery, Tsenden monastery, located in Sog county, dates back nearly 350 years. It was founded by the 5th Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso, and closely resembles that of the Potala Place in its design. The monastery was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), and was rebuilt by the local Tibetan community in the mid-1980s.

Namgyal Tseltrim remains under close surveillance by authorities, and is required to register with the local police department every month.

TIBETAN MONKS TORTURED AND IMPRISONED, ACCUSED OF MAKING COPIES OF TIBETAN FLAG

On June 6, 2008, amidst a wave of peaceful protests that was sweeping across the Tibetan plateau, three Tibetan monks from a local monastery in Draggo (Chinese: Luhuo) county, made copies of the banned Tibetan national flag and began distributing them in Draggo county town. The three monks, Tsewang Dakpa, Thupten Gyatso, from Tawu (Chinese: Dawu) county, Kardze TAP, and Shangchup Nyima, from Dzato (Chinese: Zaduo) county, Yushul (Chinese: Yushu) TAP, Qinghai province, were arrested by local security forces and accused of conducting “separatist activities.” The three were detained and interrogated for one month in Draggo prison, where one local visitor confirmed that the three were beaten and tortured during interrogation.

The monks were then transferred to Dartsedo (Chinese: Kangding) county, where they were detained for another month before the Kardze Intermediate People’s Court in Dartsedo county town sentenced them on August 23, 2008. Tsewang Dakpa was given a five year prison term, while Thupten Gyatso received four years, and Shangchup Nyima was sentenced to three years, respectively. Sources in Tibet believe that Thupten Gyatso and Shangchub Nyima were released in 2011 and 2012, when their respective sentences were up, but this could not be confirmed.

Tsewang Dakpa was released from Mianyang prison in 2013.

MONKS STILL IN ‘CRITICAL CONDITION’ AFTER IMPRISONMENT

Monks Lobsang Ngodrup, 34, and Soepa, 36, from Sershul county (Chinese: Shiqu) Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan province, the Tibetan area of Kham, were released from prison on March 10, 2013, five years after participating in what became the beginning of the largest wave of Tibetan protests in 50 years.

Both Lobsang Ngodrup and Soepa remain in critical condition due to the torture and harsh interrogation they endured in prison. Lobsang Ngodrup is currently seeking treatment at a hospital in Xining, the capital of Qinghai province, while Soepa continues to suffer psychological trauma while living at his monastery in Sershul.[42]

Lobsang Ngodrup and Soepa were among 14 Tibetans detained in a demonstration in front of the Jokhang temple in Lhasa, protesting in response to the government’s security crackdown on a peaceful Tibetan protest held earlier that day, March 10, 2008.

The Lhasa Intermediate People’s Court later sentenced those 14 to varying prison terms. Lobsang Ngodrup and Soepa were both sentenced to five years imprisonment on charges of “separatism” and incarcerated at Chushur prison, the main detention center for political prisoners in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Lobsang Ngodrup is a monk from Bon monastery and Soepa is a monk from Mange monastery in Sershul county. At the time of their arrest, both monks were in Lhasa to study at Sera monastery, one of the three main monasteries located in Lhasa, along with Drepung and Ganden.

Following their release, Lobsang Ngodrup and Soepa were returned to their home area in Sershul county, Sichuan province, under police escort. Shortly afterwards, Soepa was detained by police in Sershul county for four days, and later again in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, for a week, requiring Soepa’s family to appeal to authorities for his release. Both Lobsang Ngodrup and Soepa were required to register with officials from the local United Front Work Department.

Two other Tibetans who were among the 12 sentenced along with Lobsang Ngodrup and Soepa are known to be still in prison. Sonam Dakpa, a monk, and Dashar, a layperson, were sentenced to 10 years imprisonment on the same charges as Lobsang Nyedup and Soepa, and are currently serving their sentences in Chushur.

HUNDREDS OF LOCALS WELCOME MONK KNOWN FOR DEFENSE OF RELIGION AND CULTURE AFTER RELEASE

Hundreds of local Tibetans welcomed monk Sungrab Gyatso home on May 21, 2013, following his early release from a three-year prison sentence following involvement in peaceful protests and promotion of Tibetan language and culture.

Sungrab Gyatso, a Tibetan Buddhist monk and editor of a Tibetan-language newspaper called ‘The Path of Hope’, was likely to have been granted an early release from Dingxi prison in Gansu province due to fears that he might die in prison following severe torture during his detention, according to Tibetans in exile.

He had been serving a three-year prison sentence after authorities accused him of organizing and participating in peaceful protests in 2008 and 2010 in his home area of Machu (Chinese: Maqu) county, Kanlho (Chinese: Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (TAP), Gansu province.[43]

Sungrab Gyatso faced severe torture during his detention, causing health complications, including kidney damage. It is common for prison authorities to release prisoners with severe health difficulties in order to avoid the prisoner’s death while in their custody.

Sungrab Gyatso was arrested on August 20, 2010 by Public Security Bureau (PSB) officials and held in detention in Tsoe (Chinese: Hezuo) City, Gannan TAP, where he was interrogated and tortured for nearly two months. On October 16, 2010, the Gannan People’s Intermediate Court sentenced him to three years imprisonment.

Sungrab Gyatso had been detained two previous times, both during the widespread security crackdown that followed the wave of overwhelmingly peaceful Tibetan protests in 2008. On March 17, 2008, he was detained by the Kanlho TAP Public Security Bureau for one week, and held without charge before being released. Nearly a month later, on April 18, 2008, he was detained in Barkham (Chinese: Ma’erkang) county, Ngaba (Chinese: Aba) TAP, Sichuan, before being released several weeks later, again without charge.

Sungrab Gyatso had been active in efforts to promote the use of the Tibetan language, including teaching Tibetan language classes to local children who were previously unable to attend school in Mura township.

Sungrab Gyatso, 37, was born in Mura township, Machu (Chinese: Maqu) county, Kanlho TAP. He is a monk at Mura monastery (also known as Mura Samten Chokorling monastery).

MONK BLIND IN ONE EYE AFTER IMPRISONMENT FOLLOWING PROTESTS IN NGABA

Tenpa Gyatso was welcomed home by a large crowd of Tibetans on March 29, 2013, upon release from a five-year prison sentence after local authorities accused him of being an organizer of a protest in Ngaba on March 16, 2008.

Tenpa Gyatso, a monk from Taktsang Lhamo Kirti monastery, suffered torture and abuse during weeks of interrogation following the protests against Chinese rule by local people and monks on March 16, 2008, in Ngaba (Chinese: Aba) county town, Ngaba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan province.

The Ngaba Intermediate People’s Court in Barkham (Chinese: Ma’erkang) county town sentenced Tenpa Gyatso to five years imprisonment on March 29, 2008, which he served in Mianyang prison, outside Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. Today, Tenpa Gyatso is nearly blind in one eye due to mistreatment during his detention and imprisonment.

On March 16, 2008, a large crowd of Tibetans had taken to the streets in Ngaba county town, calling for the return of the Dalai Lama and for him to live a long life. At least 10 Tibetans – including a 16-year old schoolgirl, Lhundup Tso – were shot dead when police opened fire on the protestors.

In the crackdown that followed, numerous monks and laypeople were detained, including Tenpa Gyatso. Most were released after a few weeks or months in detention. In addition to Tenpa Gyatso’s five-year prison sentence, however, two Taktsang Lhamo Kirti monks, named Kunchok Dakpa and Kunchok Tsultrim, were sentenced to three years imprisonment. They were released in 2011, also from Mianyang prison.

Tenpa Gyatso, age 32, was born in Upper Shangsa village, Akyi township, Dzoege (Chinese: Ru’ergai) county, Ngaba TAP, Sichuan.

TIBETAN HELD FOR YEAR WITHOUT CHARGE AFTER POLICE RAID IN WHICH BROTHERS KILLED

Yonten Sangpo was released on April 21, 2013, after being detained for more than a year without charge after a police raid on his home. In February, 2012, police raided his home and shot his two brothers dead, injuring Yonten Sangpo, his mother and children.[44] According to Tibetan sources, Yonten Sangpo was threatened with life imprisonment and even execution while in detention before his release.

Officials had conducted the raid while looking for organizers of a protest held earlier in Draggo (Chinese: Luhuo) county, Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan. Exemplifying the extra-judicial punishment Tibetans are routinely subjected to, Yonten Sangpo was held for over a year without charge, and continues to struggle with severe jaw and spine injuries he suffered during the raid.

LONG-SERVING POLITICAL PRISONERS RELEASED IN 2013

LOBSANG TENZIN

On May 4, 2013, Lobsang Tenzin, one of the most high-profile Tibetan political prisoners, was released from Chushur prison in Lhasa. After 25 years in detention, he was Tibet’s longest current serving political prisoner at the time of his release.

Originally from the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, Lobsang Tenzin was a student at Tibet University when on March 5, 1988, he participated in a large-scale protest. Amidst the response to the protest by security personnel, a police officer fell from a window and died. Government officials eventually charged Lobsang Tenzin, along with four other Tibetans, with pre-meditated murder in the officer’s death and was sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve in January 1989. Lobsang Tenzin’s sentence was eventually commuted to 20 years imprisonment in April 1993.

While in prison, Lobsang Tenzin faced severe punishment and torture. In 1991, while interred at Lhasa’s infamous Drapchi prison, then the main detention center for political prisoners in the Tibet Autonomous Region, Lobsang Tenzin and his friend Tenpa Nyindak, attempted to pass on a letter to the visiting US Ambassador, James Lilly. When discovered by the authorities, the two men were severely tortured, beaten, and transferred to another prison. In all, Lobsang Tenzin served his 25-year sentence at six different prison facilities in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Now 47-years old, Lobsang Tenzin is believed to be in poor health after years of abuse and neglect while in prison.[45]

JIGME GYATSO

One of Tibet’s longest-serving political prisoners, Jigme Gyatso, was released from prison on March 31, 2013, after 17 years. Images received from Tibet show Tibetans waiting to receive him with khatags (white blessing scarves) to indicate respect and welcome him back to his home area in the Tibetan area of Amdo following his release. He was described as “very weak” upon arrival back to Sangchu (Chinese: Xiahe) county in Gansu province’s Kanlho (Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, where he had been a monk at Labrang Tashikyil monastery before his imprisonment in 1996. There are now serious concerns for his health, which is believed to be critical, and his psychological well-being.[46]

During his imprisonment, the former monk endured severe torture on several occasions. Originally sentenced to 15 years on November 23, 1996, Jigme Gyatso received the longest sentence of a group of five Tibetans who carried out various acts of peaceful resistance, including putting up a Tibetan national flag at Ganden monastery and raising the issue of Tibetan independence. The sentencing document issued by the Lhasa Intermediate People’s Court makes it clear that Jigme Gyatso was regarded by the Chinese authorities as the ring-leader. At the time of his arrest in March 1996, he was running a restaurant in Lhasa after leaving Ganden monastery.

When he was first detained in March 1996, he was held at Gutsa detention center in Lhasa prior to his sentencing. A friend of Jigme Gyatso’s who is now in exile told ICT: “Jigme Gyatso was severely tortured at Gutsa. He was held in a dark room, separate to about 17 other Tibetans who were detained at the same time. He was kept in heavy shackles.”